As an American living in Britain in the 1990s, my first exposure to Christmas pudding was something of a shock. I had expected figs or plums, as in the “We Wish You a Merry Christmas” carol, but there were none. Neither did it resemble the cold custard-style dessert that Americans typically call pudding.

Instead, I was greeted with a boiled mass of suet — a raw, hard animal fat that is often replaced with a vegetarian alternative — as well as flour and dried fruits that is often soaked in alcohol and set alight.

It’s in no danger of breaking into my top 10 favorite Christmas foods. But as a historian of Great Britain and its empire, I can appreciate the Christmas pudding for its rich global history. After all, it is a legacy of the British Empire with ingredients from around the globe it once dominated and continues to be enjoyed in places it once ruled.

Christmas Pudding Takes Its Shape

Christmas pudding is a relatively recent concoction of two older, at least medieval, dishes. The first was a runny porridge known as “plum pottage” in which any mixture of meats, dried fruits and spices might appear — edibles that could be preserved until the winter celebration.

Until the 18th century, "plum” was synonymous with raisins, currants and other dried fruits. “Figgy pudding,” immortalized in the “We Wish You a Merry Christmas” carol, appeared in the written record by the 14th century. A mixture of sweet and savory ingredients, and not necessarily containing figs, it was bagged with flour and suet and cooked by steaming. The result was a firmer, rounded hot mass.

During the 18th century, the two crossed to become the more familiar plum pudding — a steamed pudding packed with the ingredients of the rapidly growing British Empire of rule and trade. The key was less a new form of cookery than the availability of once-luxury ingredients, including French brandy, raisins from the Mediterranean, and citrus from the Caribbean.

Few things had become more affordable than cane sugar, which, owing to the labors of millions of enslaved Africans, could be found in the poorest and remotest of British households by mid-century. Cheap sugar, combined with wider availability of other sweet ingredients like citrus and dried fruits, made plum pudding an iconically British celebratory treat, albeit not yet exclusively associated with Christmas.

Such was its popularity that English satirist James Gillray made it the centerpiece of one of his famous cartoons, depicting Napoleon Bonaparte and the British prime minister carving the world in pudding form.

In line with other modern Christmas celebrations, the Victorians took the plum pudding and redefined it for the holiday season, making it the “Christmas pudding.”

In his 1843 internationally celebrated “A Christmas Carol,” Charles Dickens venerated the dish as the idealized center of any family’s Christmas feast: “Mrs Cratchit entered — flushed, but smiling proudly — with the pudding, like a speckled cannon-ball, so hard and firm, blazing in half of half-a-quarter of ignited brandy and bedight with Christmas holly stuck into the top.”

Three years later, Queen Victoria’s chef published her favored recipe, making Christmas pudding, like the Christmas tree, the aspiration of families across Britain.

Christmas pudding owed much of its lasting appeal to its socioeconomic accessibility. Victoria’s recipe, which became a classic, included candied citrus peel, nutmeg, cinnamon, lemons, cloves, brandy and a small mountain of raisins and currants — all affordable treats for the middle class. Those with less means could either opt for lesser amounts or substitutions, such as brandy for ale.

Eliza Acton, a leading cookbook author of the day who helped to rebrand plum pudding as Christmas pudding, offered a particularly frugal recipe that relied on potatoes and carrots.

White colonists’ desires to replicate British culture meant that versions of Christmas pudding soon appeared across the empire. Even European diggers in Australia’s goldfields included it in their celebrations by mid-century.

The high alcohol content gave the puddings a shelf life of a year or more, allowing them to be sent even to the empire’s frontiers during Victoria’s reign, including to British soldiers serving in Afghanistan. Christmas celebrations for British soldiers fighting in the Crimea in 1855 included the Christmas pudding — a welcome respite from the cold winter.

Empire Pudding

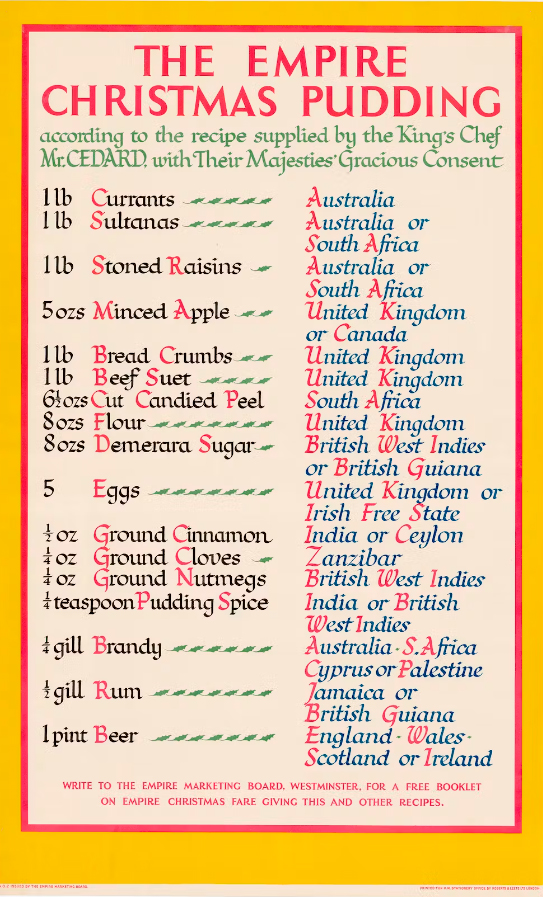

In the 1920s, the British Women’s Patriotic League heavily promoted it, calling it “Empire Pudding” in a global marketing campaign. They praised it as emblem of the empire that should be made from the ingredients of Britain’s colonies and possessions: dried fruits from Australia and South Africa, cinnamon from Ceylon, spices from India and Jamaican rum in place of French brandy.

Press coverage of London’s 1926 Empire Day celebrations featured the empire’s representatives pouring the ingredients into a ceremonial mixing bowl and collectively stirring it.

The following year, the Empire Marketing Board received King George V’s permission to promote the royal recipe, which had all the appropriate empire-sourced ingredients.

Such promotional recipes and the mass production of puddings from iconic grocery stores like Sainsbury’s in the 1920s combined to place Christmas puddings on the tables of a myriad of peoples who resided across an empire on which the sun never set.

After The Empire

Decolonization did not diminish the appeal of the Christmas pudding. Passengers transiting through London’s airports can find them in abundance this time of year. Their shape and density have baffled airport security scanners for some time, leading to requests to carry them as hand luggage.

In former white settler colonies, like Canada, the tradition endured, although in Australia, where Christmas falls in summer, trifle and pavlova are at least equally common. In parts of India, where it is sometimes known as “pudim,” it remains a traditional favorite, “steeped in tradition,” according to the leading English national daily newspaper, the “Hindustan Times.”

Reflecting modern palates and trends, Jamie Oliver, the celebrated British chef and author, has gluten-free and more modern options this year. His “classic” recipe, however, would not have been out of place on Queen Victoria’s table.

Like so many adaptations around the former empire, it includes some American ingredients: pecans and cranberries as well as bourbon substituted for brandy — an Anglo-American concoction — much like my own family. And I will embrace this one.

This story was originally published by The Conversation.