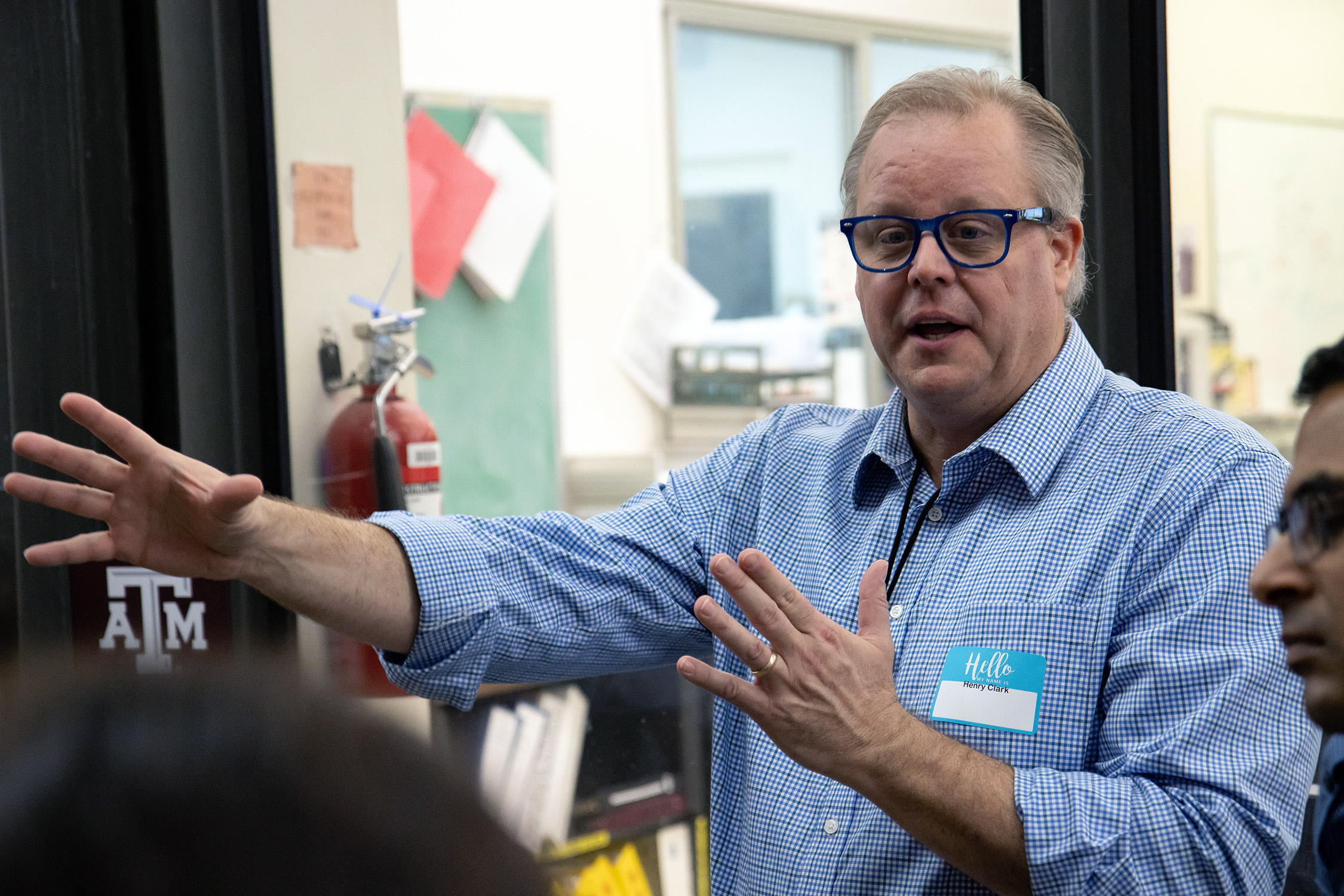

When Dr. Henry L. Clark initially arrived in Aggieland in 1993, fresh off getting his Ph.D. in nuclear physics from Ohio University and research experience at four U.S. Department of Energy national laboratories along the way, he had no idea one of his future job responsibilities would be to come up with the next big Texas A&M University tradition.

“After completing a postdoctoral research appointment doing fundamental science in the Cyclotron Institute, one of my first jobs as an accelerator physicist in the Operations Group was to develop a program for testing electronics for space,” Clark recalled. “Now, we're the world leader at it.”

For three decades and counting with Clark at the facility supervisory lead, the Cyclotron Institute has provided high-energy heavy ion particle testing unmatched in its ability to accurately simulate the effects of space radiation. Unlike X-ray and other testing techniques that cannot fully capture the complexities of space conditions, Texas A&M’s testing represents the gold standard for understanding the true impacts of space radiation on electronic systems — an essential factor in developing space systems capable of withstanding the rigors of extended missions, particularly in the increasingly competitive and strategically significant domains of earth orbit as well as lunar- and deep-space exploration.

Since its founding in 1995, the Cyclotron Institute’s radiation effects testing program has grown to encompass nearly 5,000 hours of dedicated beam time each year, establishing Texas A&M as the premier location in not only the U.S. but also the world at which to do testing of heavy ion interactions with electronics, an important safeguard for both commercial and military satellites as well as space missions. Each year, more than 500 users come to the institute for these critical studies, perhaps none more memorable than SpaceX and the pivotal testing for nearly 100 electronic components of its Crew Dragon capsule that made history in 2020 as the first crewed spacecraft to lift off from American soil since 2011.

“We’re not the world leader because we planned it this way,” Clark explained. “We are the world leader because we could do it, and we did do it. We're still doing it, and we do it better than anyone else.”

The Readout on Radiation

Radiation can impact space missions, satellites, airplanes and many other phenomena that rely on everyday electronics. While some devices may experience errors that can be cleared by restarting the system, others may encounter more significant failures that can prove to be destructive or even fatal. Before sending critical devices beyond the Earth’s surface, it’s important to test such components to understand their failure modes and bound risks.

“Anything that flies in space has to deal with the natural space radiation environment, whether it's solar wind particles coming off the sun, trapped particles, which are intense because of the Earth’s magnetic field, or galactic cosmic rays,” Clark added.

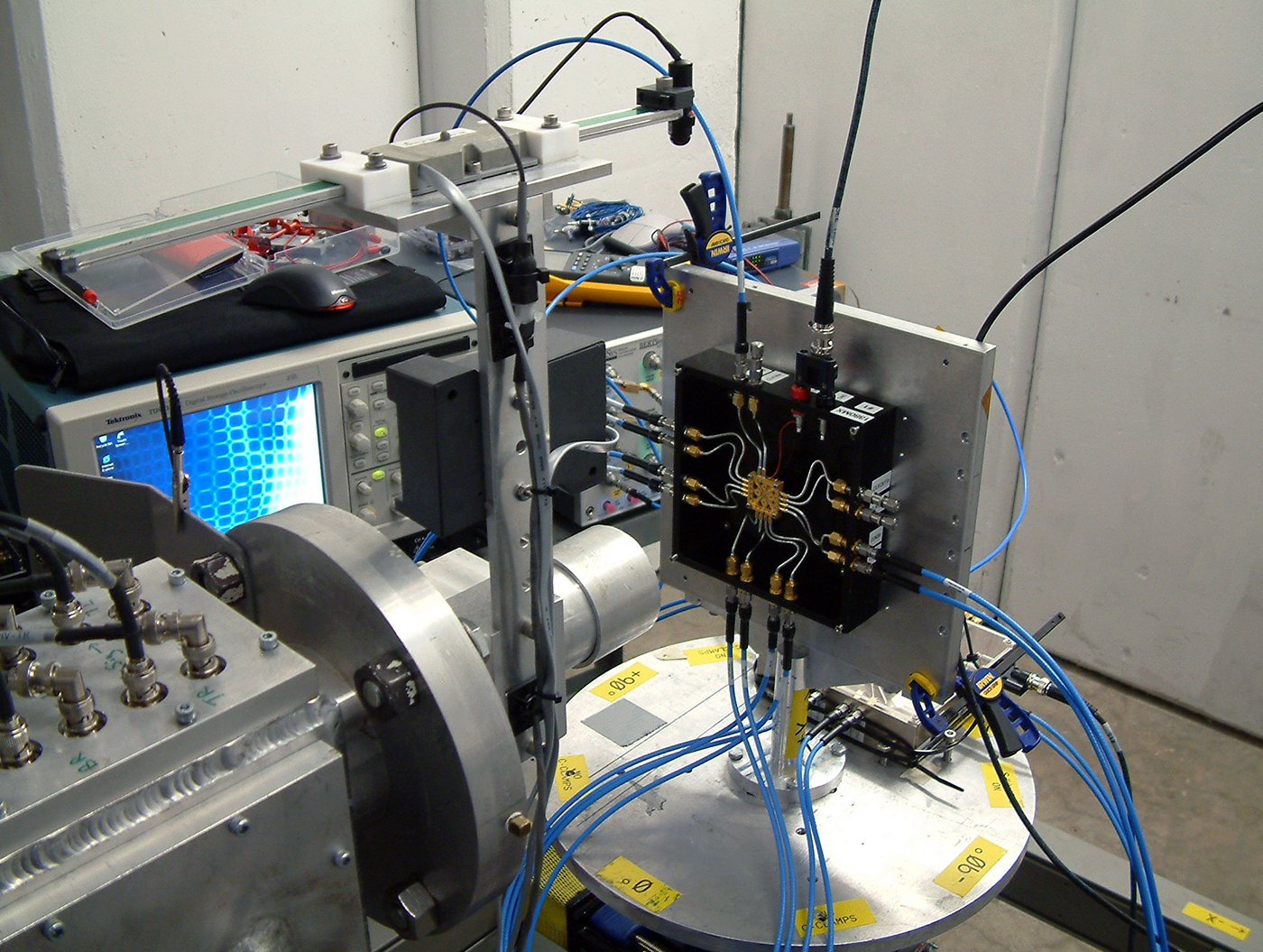

The main issue electronics face with space radiation is the single-event effect (SEE), which Clark says occurs when a single high-energy particle infiltrates an integrated circuit and causes corruption or even permanent damage. As electronic devices have gotten smaller in the digital age of component miniaturization, they also have become more sensitive to radiation.

“Essentially, all the layers of a circuit board, which may have been several boards in years past, are now one small integrated circuit,” he added. “That means a radiation ion can go through all the devices at one time and destroy the whole thing. So, it's catastrophic. And as parts continue to get smaller, the problem gets worse.”

SEE testing helps clients take some of the guesswork out of how their new technology will perform in the harsh environment of outer space by determining how effectively the equipment can withstand cosmic radiation at a mission-critical juncture: before it is launched.

“Because we here at the Cyclotron Institute can create the same radiation that exists in space with our accelerators, companies can test their electronics here before ever sending them into space,” Clark added. “Such precautions potentially save time, money and, in some cases, even human lives. It’s very exciting to see that Texas A&M is contributing to such invaluable efforts benefiting so many sectors, from space exploration and research to security and defense.”

If You Build it

Texas A&M’s radiation effects testing program originated as one of many futuristic possibilities envisioned by former Cyclotron Institute director and physicist Dr. Dave Youngblood. The program became a reality during nuclear chemist Dr. Joseph B. Natowitz’s time as director, when the institute began receiving some of its first testing requests from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration's (NASA) Johnson Space Center in relation to the Space Shuttle program. As technology continued to evolve and rely on increasingly smaller and more complex circuitry, the program hit its stride in the early 2000s under the leadership of then-director and physicist Dr. Robert E. Tribble, who capitalized on his own possibility to position the institute at the global cutting edge.

In the beginning, however, Clark admits he helped pioneer the institute’s testing program as a viable means of filling time on its then-comparatively sparse beam schedule.

“We started doing the testing operation as a way of using the excess time, because, to quote one of my favorite sayings: ‘If you turn the accelerators off, you don't know if they're broken,’” Clark explained. “At that time, the machine didn’t need to operate twenty-four seven for science-program purposes, but we realized we could do some applied work in addition to the fundamental science if we increased our operations to take advantage of the opportunity.”

Even in its pre-SEE-testing days, Clark says the Cyclotron Institute had its own applied program in cancer therapy in partnership with MD Anderson Cancer Center — a collaboration that continues today through the institute’s medical isotope program that supplies astatine-211 to MD Anderson and other nearby facilities for their own fundamental research and radiopharmaceutical development.

“Back then, we actually made neutron beams for cancer therapy research,” he added. “While I don't think there was any cancer that was solved, the cancer therapy program that we had here gave people more time in their lives. What MD Anderson learned from that program was how to build the right accelerator for the right application for medical physics. And we learned that we could benefit from complementary programs in fundamental discovery science and applied accelerator physics.”

A First-Rate Facility

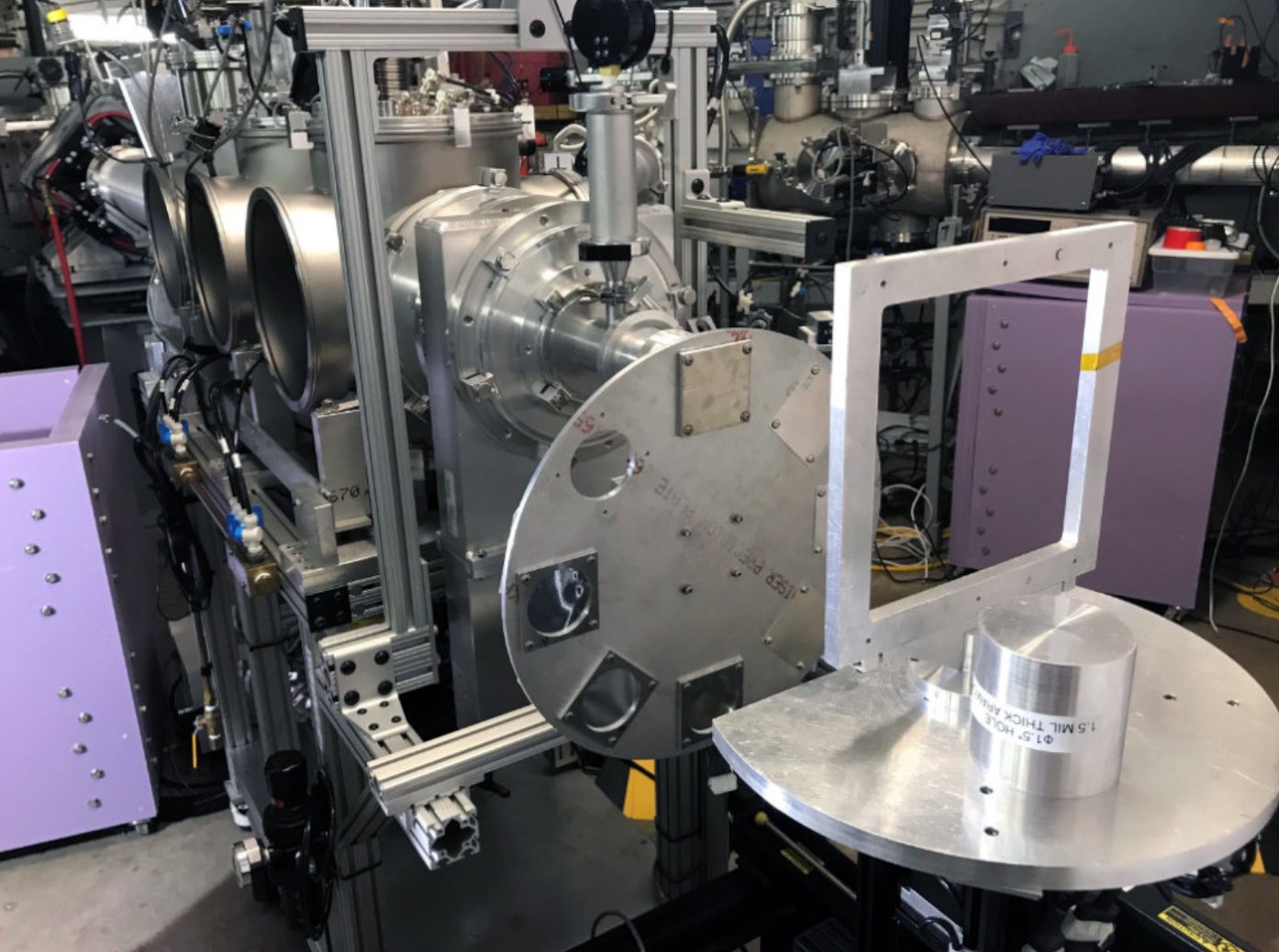

Through its Radiation Effects Facility (REF), the Cyclotron Institute continues to provide a convenient and affordable testing solution for commercial, government and educational entities in need of the capabilities to study, test and simulate the effects of ionizing radiation on electronic and biological systems used in various aerospace, defense and industrial applications. In addition to a dedicated beam line, users have access to a climate-controlled data room and a staging area that includes tables and work benches for test preparation and setup.

The lynchpin of the facility and its testing capabilities is the K500 superconducting cyclotron, which was constructed by Cyclotron Institute scientists and commissioned in 1987 and ranks as one of the five largest in the world. Paired with the institute’s original K150 cyclotron, which was completely refurbished in the late 2000s, the two respectively produce high-energy ion beams — from helium up to and including gold — along with proton beams. These beams weave through an intricate configuration of sophisticated spectrometers and guides within the 49,000-square-foot facility that track critical information about the energies and results passing through them. For roughly 10,000 hours each year, those ion beams zip at near-light speed under the watchful eye of scientists and technicians who closely monitor the sensitive diagnostic and specialized components that keep both accelerators in motion and in demand for a bevy of external clients and research collaborators.

"Forty-five years ago, those planning the K500 cyclotron had no idea that we would be doing this now,” Clark said. “But they were intuitive enough to know they needed to build something that was scalable and expandable, thereby giving us the possibility to evolve to solve problems that we didn’t even know existed at the time.”

One additional feature of the K500 that sets it apart from most other cyclotrons is its ability to test the radiation effects of ion beams on equipment without the use of a vacuum, saving valuable time and money. While low-energy cyclotrons require nearly an entire day for equipment setup and testing inside a vacuum chamber, Clark says that the K500’s in-air testing feature requires only a third of that time, piquing the interest of many national organizations, defense and otherwise.

“Our machines are what are known as variable-energy machines, meaning they make a wide range of particles over a wide range of energies, which is very uncommon,” Clark added. “Most accelerators make one particle of one energy, so we're like one-stop shopping. Plus, we can give a wide range of electron-hole [pair] or energy punches to silicon devices or microchips, just by changing the beams coming out of the accelerator.”

We’re not the world leader because we planned it this way. We are the world leader because we could do it, and we did do it. We're still doing it, and we do it better than anyone else.

SEEing the Possibilities

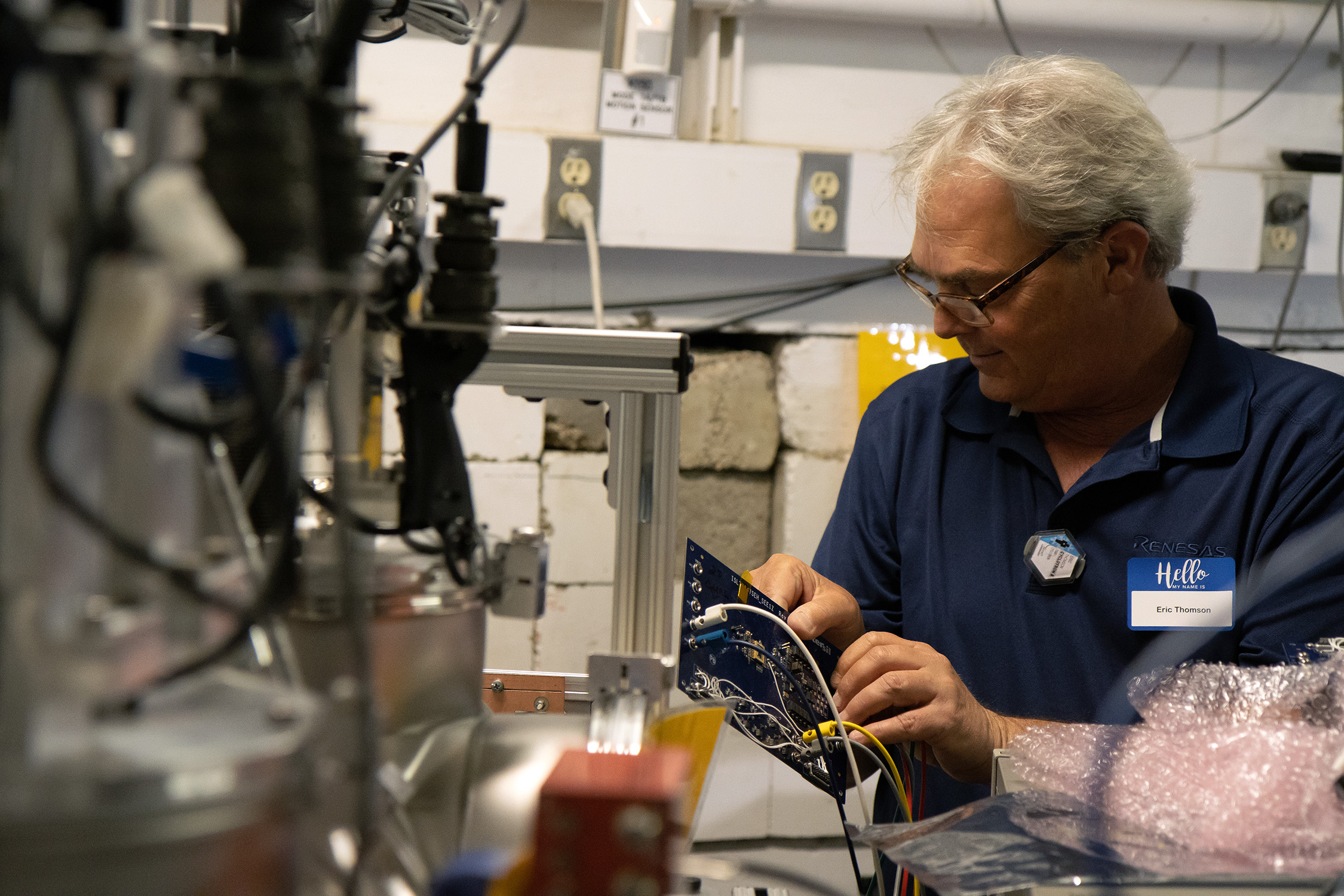

Approximately 30 staff members alternate round-the-clock shifts to oversee the facility and meet the needs of the campus research community as well as those of roughly 200 companies and agencies — including SpaceX, Northrop Grumman, Lockheed Martin, Texas Instruments, Renesas Electronics and Honeywell — that use experimentation time on the equipment for their own research projects. In combination, their use accounts for more than $5 million each year in support of the infrastructure that helps to generate in excess of $18 million annually in overall external funding for the institute.

In 2022, the U.S. Department of Defense awarded an $11 million grant to the Cyclotron Institute for facility improvements to enhance the facility’s chip-testing capacity — the most recent in a strong tradition of federal-, state- and privately-funded renovations to advance the institute’s overall three-part mission of discovery science, workforce development and societal application.

“We're in the process of upgrading the K150 cyclotron to create more heavy ions, because that's where the effects are,” Clark said. “It's the single-event effect that everyone is really interested in, and if we can make more heavy ions with this machine, we'll be able to provide more beam time to the industry.”

In addition to critical testing services, the REF also features educational and professional development opportunities. For instance, graduate students pursuing master’s degrees in physics can select radiation effects as a focus area and gain hands-on experience with research projects involving some of the very experts they may one day be hired to work alongside in this rapidly growing field.

“A 2018 National Academies study, Testing at the Speed of Light, identified a variety of needs for the radiation effects community, including workforce development programs to counter the shortage of people going into the radiation effects testing field and additional testing time for users in government, industry and academia,” said Texas A&M Distinguished Professor and Regents Professor of Chemistry Dr. Sherry J. Yennello, who has served since 2014 as director of the Cyclotron Institute. “As a university, we decided that was something we needed to do for the nation — to build a program to help fill that workforce need. We partnered with NASA to put together a master’s of science program in applied physics within the Department of Physics and Astronomy so that, as the nation moves forward, we have both the facilities like the Cyclotron Institute as well as the workforce capable of designing and interpreting those tests to ensure that, when we launch things into space, we are confident in their ability to withstand the very harsh radiation environment they will encounter."

In Service of Nuclear Science

When it comes to sharing his time, talents and knowledge to give back to the profession and broader scientific community, Clark says it’s both an opportunity and a challenge that never gets old for him or his fellow scientists, regardless of the day, decade or experiment design at hand.

“We fell into this at the right time with the right group of people,” Clark added. “I came here at the right time. The facility was growing at the right time. The ability to provide beams for the industry came at the right time.

“We came in, we built our accelerator, we developed our accelerator program and we were able to provide these things. As we were able to develop different beams and the ability to change them quickly by developing custom methods, we found that the industry needed these things. And we just kept on moving with industry."

Barring any technical hiccups, the cyclotrons run 24 hours per day, seven days a week for 10 months. The other two months of the year are scheduled for cyclotron and beam line maintenance. Every piece of equipment is inspected, and components that are suspected of possible failure are replaced.

“There is nowhere else in the world that runs these kinds of hours day after day, year-long, especially in a university setting,” Clark said. “We have great talent here from all over the world — dedicated staff who have the creative ideas, know what they are doing and know how a high-tech facility should run.”

Visit cyclotron.tamu.edu/ref/ to learn more or schedule beam time.

About The Cyclotron Institute

The Cyclotron Institute, a U.S. Department of Energy University Facility and one of five DOE-designated Centers of Excellence, is jointly supported by the DOE and the state of Texas as a major technical and educational resource for the state, nation and world. Internationally recognized for its research, the institute provides the primary infrastructure support for Texas A&M’s graduate programs in nuclear science. In addition to conducting basic research and educating students in accelerator-based science and technology, the institute provides technical capabilities for a wide variety of applications in space science, materials science, analytical procedures and nuclear medicine.