-

The Revolutionary Upheaval in the Middle East and North Africa

Dr. Gilbert Achcar, London School of Oriental and African Studies

Ten years will soon have passed since the Arab Spring started in Tunisia in December 2010 before spreading like wildfire to the whole MENA region, with major uprisings in five other countries in 2011. Three years later, it looked however as if the spring had turned into winter and regional revolutionary prospects were drowned in counter-revolutionary backlashes and/or civil wars. And yet, December 2018 saw the beginning of a new revolutionary upsurge that started in Sudan and spread to three other countries in 2019, before being stifled by the Covid-19 pandemic. Still, the second wave was a powerful confirmation of the view that what started ten years ago was deeply rooted in a structural crisis affecting the region’s economic, social, and political features. It also confirmed therefore the view that the 2011 Arab Spring was but the beginning of a long-term revolutionary process that will inevitably carry on through successive phases of upsurge and backlash, and will not give way to a new long-term stabilization short of radical structural change.

November 11, 2020

Wednesday, 12–1:30pm

Zoom session

Meeting ID: 955 1955 9711

Passcode: 514966If you cannot join with video, you can connect to the Zoom session via phone: 1–346–248–7799

-

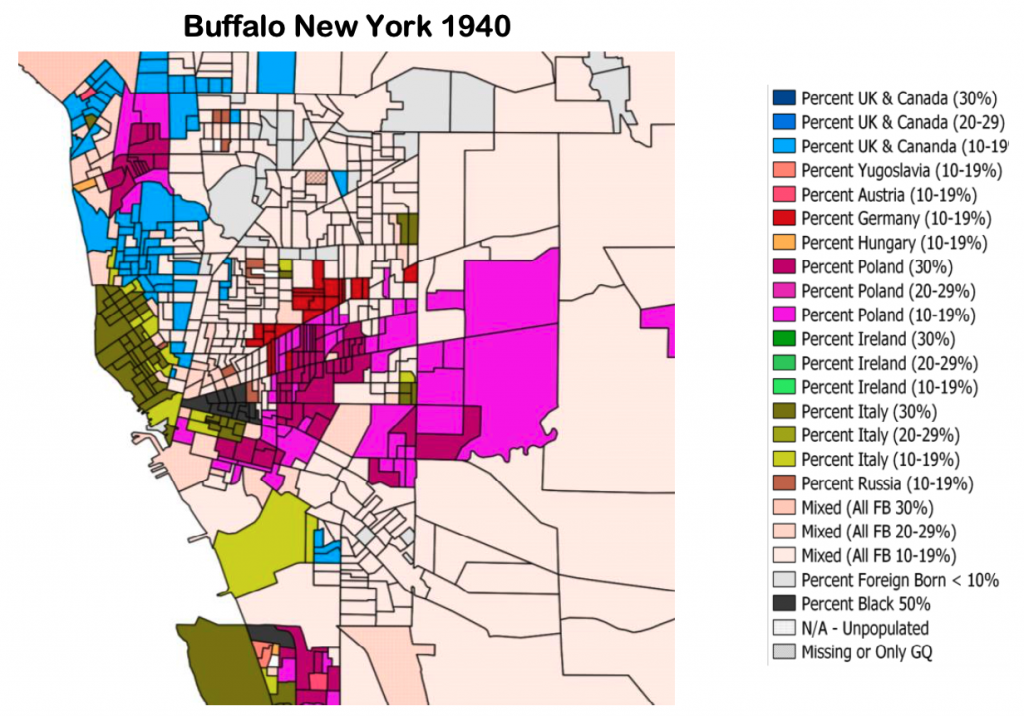

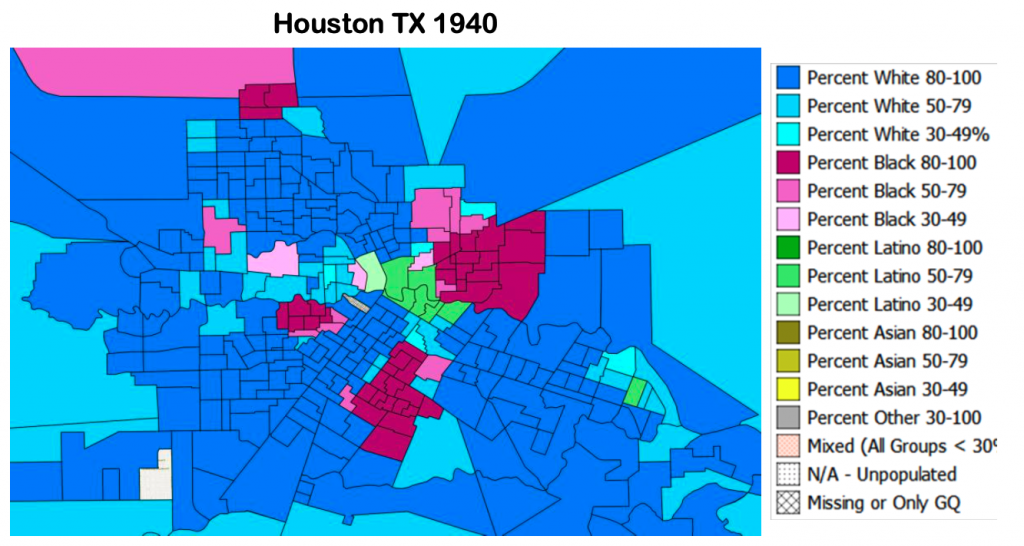

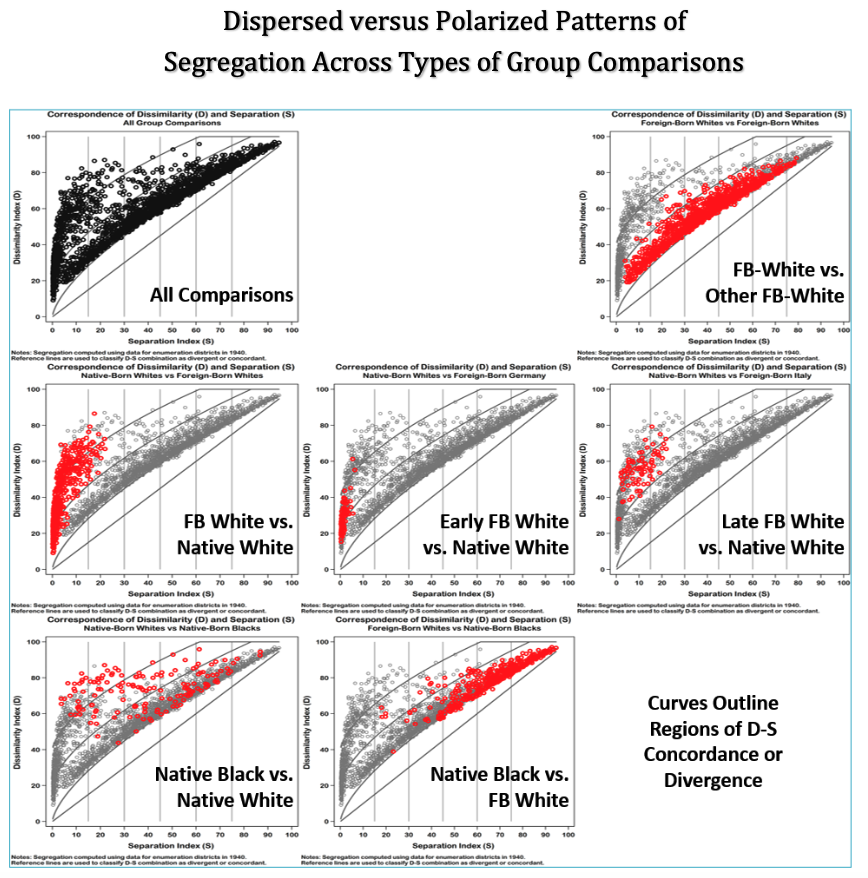

Residential Segregation of Racial-Ethnic Groups in 1940: Findings and Opportunities Based on Analyzing Restricted Microdata

Dr. Mark Fossett, Texas A&M University

I will present selected findings from research in progress investigating residential segregation of racial-ethnic groups in US urban areas in 1940. The research draws on a rich new data source – restricted IPUMS microdata files from the 1940 US decennial census. These data permit refined quantitative analysis of the level and nature of segregation for European immigrant groups and racial minority groups in US urban areas in 1940 not previously possible. I will review findings from analysis of segregation patterns for more than 2,400 pair combinations involving Native-Born Whites, Foreign-Born Whites by country of origin, and Native-Born Non-White groups.

Segregation patterns for this era have never been studied quantitatively due to limits of available data, methods, and computing power. Old assumptions about patterns circa-1940 and before are often based on thin empirical analysis. Analysis using restricted microdata for 1940 yield interesting findings regarding both the levels and the forms of segregation patterns and how they vary across group comparisons. Some may find selected results surprising: (1) White- Asian segregation in 1940 is much higher than that seen today, (2) White-Black segregation is surprisingly low in many metro areas and often follows a pattern different from what most would presume, (3) European immigrant populations have moderate-to-low segregation from native-born whites, but very high levels of segregation from native-born blacks and from each other, and (4) Due to back-alley segregation patterns, some patterns of white-minority “integration” are deceptive and involve white-minority contact between high-status whites and lower status minority households (e.g., domestic service workers).

I will devote a portion of my presentation to reviewing opportunities students have to conduct leading edge research on residential segregation using historical IPUMS microdata and contemporary restricted microdata files available through in the TXRDC.

The distinction between dispersed and polarized patterns of segregation is important, but it is not widely appreciated. Under polarized displacement from even distribution groups are separated into ethnically homogeneous neighborhoods. This is a prerequisite for segregation to have important implications for group stratification. It is generally assumed but in fact it is not always present. Instead, segregation may involve dispersed displacement from even distribution wherein some segregation indices take high values but close analysis reveals the groups generally live together and experience similar neighborhood conditions. These two patterns vary across group comparisons.

Fossett, Mark. 2017. New Methods for Measuring and Analyzing Segregation. Cham: Springer.

November 4, 2020

Wednesday, 12–1:30pm

Zoom session

Meeting ID: 944 4649 3967

Passcode: 927160If you cannot join with video, you can connect to the Zoom session via phone: 1–346–248–7799

-

The Effects of Income on Birth Rates: The Case of a Universal Cash Transfer

Dr. Sarah K. Cowan, New York University

Governments around the globe institute income policies in order to alleviate poverty. Whether these policies have unintended fertility effects is an open question, and the answer has implications for fertility theory, policy design and inequality. This question has been addressed in prior literature primarily by examining the introduction of means-tested relief to families with children. This limits analysis to families in poverty and provides insight only into the presence or absence of a policy. We overcome these weaknesses by examining the Alaska Permanent Fund Dividend, which has provided all Alaskan residents with a substantial annual cash payment since 1982. The amount of the payment varies year to year and is exogenous to individual Alaskans’ behavior and the state’s economy. We examine the relationship between income and fertility among a large and diverse population that has received varying amounts of money over time.

October 28, 2020

Wednesday, 12–1:30pm

Zoom session

Meeting ID: 928 5222 8506

Passcode: 343142If you cannot join with video, you can connect to the Zoom session via phone: 1–346–248–7799

-

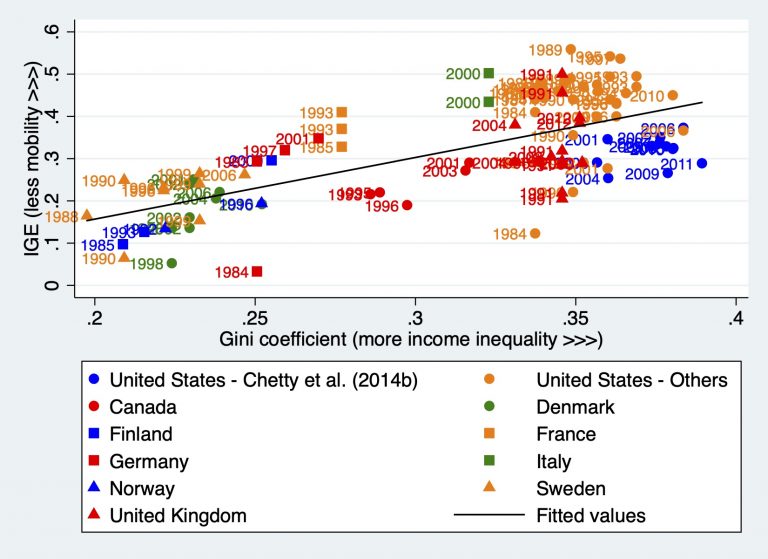

Association of Income Inequality and Migration with Intergenerational Mobility

Dr. Ernesto Amaral, Dr. Arthur Sakamoto, Shih-Keng Yen, Texas A&M University

Dr. Sharron Wang-Goodman, Delaware State University

Link to presentationA Meta-Analysis of the Association Between Income Inequality and Intergenerational Mobility

We provide an overview of associations between income inequality and intergenerational mobility in the United States, Canada, and eight European countries. We analyze whether this correlation is observed across and within countries over time. We investigate Great Gatsby curves and perform meta-regression analyses based upon several papers on this topic. Results suggest that countries with high levels of inequality tend to have lower levels of mobility. Intergenerational income elasticities have stronger associations with the Gini coefficient, compared to associations with the top one percent income share. Once models are controlled for methodological variables, country indicators, and paper indicators, correlations of mobility with the Gini coefficient lose significance, but not with the top one percent income share. This result is an indication that recent increases in inequality at the top of the distribution might be negatively affecting mobility on a greater magnitude, compared to variations across the income distribution (link to paper).

What About Immigration? The Closed-Population Assumption in Research on Intergenerational Income Mobility

Research on intergenerational income mobility is highly informative and increasingly popular. A neglected aspect of these studies, however, is their implicit target population. Research on income mobility studies are typically biased towards the representation of third-and-higher generation persons. We refer to this practice as the closed-population assumption. First-generation, second-generation, and undocumented immigrants are less likely to be included because adequate data on income for their parental generation is more likely to be missing. Given significant international migration, ignoring the foreign stock is potentially inaccurate when making generalizations about entire societies. We discuss analytical issues associated with the closed-population assumption, and provide some exploratory findings which suggest significant interrelationships between immigration and intergenerational income mobility.

October 21, 2020

Wednesday, 12–1:30pm

Zoom session

Meeting ID: 963 3738 5938

Passcode: 577241If you cannot join with video, you can connect to the Zoom session via phone: 1–346–248–7799

-

Becoming Brokers: Building Thailand’s Brand in Public Health

Dr. Joseph Harris, Boston University

From HIV prevention to universal health coverage to coronavirus response, Thailand’s public health policies have garnered international acclaim. What has enabled a resource-constrained country in the Global South to exercise such outsized influence in global public health? What mechanisms have led Thailand’s policies to travel abroad? And more broadly, how does a nation in the global periphery exercise influence in international affairs? Based on Fulbright-funded research conducted in Thailand’s Division of Global Health and the WHO in 2017-18, this talk will examine the organizational basis of Thailand’s success, its relationship to nation branding, and implications for developmental states aspiring to meet the world’s pressing health challenges. Through comparative historical analysis of four policy domains (tobacco control, access to medicine, health technology assessment, and global health diplomacy), I find autonomous non-profit and parastatal organizations to play key roles addressing complex problems and enhancing national reputation, even as they stand apart from a government that reaps the symbolic rewards.

October 14, 2020

Wednesday, 12–1:30pm

Zoom session

Meeting ID: 968 1107 6322

Passcode: 761491If you cannot join with video, you can connect to the Zoom session via phone: 1–346–248–7799

-

Examining the Causal Effect of Skin Color in Online Dating

Dr. Emilce Santana, Texas A&M University

This project seeks to measure the causal effect of an individual’s skin color on their likelihood of engaging in interethnic/interracial romantic relationships. The literature on skin color inequality is limited by issues such as a heavy reliance on observational data and inconsistent measures of skin color, which hinder researchers’ capacity to make causal inferences about the role of skin color in perpetuating discrepancies in outcomes within ethnoracial groups. To address these issues, I field a survey experiment that features online dating profiles of Black daters. I test how the skin color of the profiled individuals affects the likelihood that respondents of other ethnoracial groups will be interested in dating them. The results of this study will improve the sociological understanding of a particular mechanism that may determine contact across ethnoracial groups.

October 7, 2020

Wednesday, 12–1:30pm

Zoom session

Meeting ID: 934 2571 4176

Passcode: 425155If you cannot join with video, you can connect to the Zoom session via phone: 1–346–248–7799

-

Diversifying the UAE and Russia: How National Higher Education Policies Attract International Students

Dr. Karin Johnson, Texas Research Data Center (TXRDC)

Dr. Johnson’s core interest is in how policy can attract skilled migrants, particularly to developing areas with a low or declining population. In her recent research, Johnson compared higher education internationalization policies in the UAE and Russia that aim to recruit international students. The UAE and Russia are both oil and resource rich (and looking to diversify their national economies), but people poor (they depend on migrants to maintain the population). From expert interviews with forty-three university administrators and public officials, Johnson concluded that while Russia’s recruitment goals are to enroll students, UAE policy targets foreign institutes to come to build branch campuses. Differing outcomes are the results of the composition of international students and state motivations. In contrast to traditional destination countries, such as the US or UK, interviews revealed that an underlying agenda of global political cooperation trumps purely economic intentions to recruit foreign students. Moving forward, Johnson continues to employ mixed-method techniques to examine the relationship among international higher education, skilled migration, migrants’ transition into the labor force, policy, and demographic deficits.

September 30, 2020

Wednesday, 12–1:30pm

Zoom session

Meeting ID: 931 6886 7156

Passcode: 889202If you cannot join with video, you can connect to the Zoom session via phone: 1–346–248–7799

-

Demagogue for President: The Rhetorical Genius of Donald Trump

Demagogue for President: The Rhetorical Genius of Donald TrumpDr. Jennifer R. Mercieca, Texas A&M University

A demagogue—a leader of the people—could be a hero or a villain. What kind of demagogue is Donald Trump? He is both a hero and a villain—a hero to his supporters and a villain to everyone else.

A demagogue—a leader of the people—could be a hero or a villain. What kind of demagogue is Donald Trump? He is both a hero and a villain—a hero to his supporters and a villain to everyone else.Demagogue for President tells the story of Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign and shows how Trump took advantage of pre-existing distrust, polarization, and frustration to attack America.

Within a crisis of public trust in which the very viability of democracy was at risk, Trump ran a campaign that was designed to increase distrust for government and traditional leadership. Within a crisis of polarization in which Americans believed that they had little common ground with their political opposition, did not share the same values, and that their opposition was an enemy of the state, Trump ran a campaign that was designed to increase polarization. Within a crisis of frustration in which Americans believed that government was the biggest issue facing the nation, that the nation was on the wrong track, and that anybody else would do a better job running the country than current leaders, Trump ran a campaign that was designed to increase frustration.

Trump used rhetoric as a weapon—as a “counterpunch”—and in so doing Trump attacked America’s public sphere and its democratic process. Demagogue for President gives Americans a vocabulary to use to understand Trump’s rhetorical strategies and explains why those strategies are dangerous for democratic stability.

More here: https://www.jennifermercieca.com/demagogueforpresident

September 16, 2020

Wednesday, 12–1:30pm

Zoom session

Meeting ID: 913 4925 0255

Passcode: 492243If you cannot join with video, you can connect to the Zoom session via phone: 1–346–248–7799

-

Taking America Back for God: Christian Nationalism in the United States

Taking America Back for God: Christian Nationalism in the United StatesDr. Andrew Whitehead, Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI)

Dr. Samuel Perry, The University of OklahomaWhy do so many conservative Christians continue to support Donald Trump despite his many overt moral failings? Why do many Americans advocate so vehemently for xenophobic policies, such as a border wall with Mexico? Why do many Americans seem so unwilling to acknowledge the injustices that ethnic and racial minorities experience in the United States? Why do a sizeable proportion of Americans continue to oppose women’s equality in the workplace and in the home?

To answer these questions, Taking America Back for God points to the phenomenon of “Christian nationalism,” the belief that the United States is-and should be-a Christian nation. Christian ideals and symbols have long played an important role in American public life, but Christian nationalism is about far more than whether the phrase “under God” belongs in the pledge of allegiance. At its heart, Christian nationalism demands that we must preserve a particular kind of social order, an order in which everyone–Christians and non-Christians, native-born and immigrants, whites and minorities, men and women recognizes their “proper” place in society. The first comprehensive empirical analysis of Christian nationalism in the United States, Taking America Back for God illustrates the influence of Christian nationalism on today’s most contentious social and political issues.

Drawing on multiple sources of national survey data as well as in-depth interviews, Andrew Whitehead and Samuel Perry document how Christian nationalism shapes what Americans think about who they are as a people, what their future should look like, and how they should get there. Americans’ stance toward Christian nationalism provides powerful insight into what they think about immigration, Islam, gun control, police shootings, atheists, gender roles, and many other political issues-very much including who they want in the White House. Taking America Back for God is a guide to one of the most important-and least understood-forces shaping American politics.

September 9, 2020

Wednesday, 12–1:30pm

Zoom session

Meeting ID: 997 2258 7671

Passcode: 699330If you cannot join with video, you can connect to the Zoom session via phone: 1–346–248–7799

This event is co-sponsored with Texas A&M Religious Studies.