On April 12, 1963, Martin Luther King, Jr. was in jail along with 50 fellow activists arrested for leading a Good Friday demonstration as part of the Birmingham Campaign in the Civil Rights Movement. This was King’s 13th arrest, and would become one of the most important in his career as he penned the now famous “Letter From Birmingham Jail.”

On April 12, 1963, Martin Luther King, Jr. was in jail along with 50 fellow activists arrested for leading a Good Friday demonstration as part of the Birmingham Campaign in the Civil Rights Movement. This was King’s 13th arrest, and would become one of the most important in his career as he penned the now famous “Letter From Birmingham Jail.”

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere,” one line in the 7,000 word letter King penned in Birmingham read. King, who was incarcerated 29 times for acts of civil disobedience and on trumped up charges like going 5 mph over the speed limit, repeatedly experienced injustice in the criminal justice system.

Fifty-eight years after King’s arrest in Birmingham, we celebrate his achievements as a civil rights leader and continue his quest for equality by examining our society from a civil rights perspective. Robert Durán, an associate professor of sociology who studies criminology and race, said our criminal justice system continues to be a threat to justice today.

“Most of our societal inequalities are heightened in the criminal justice system, particularly racial and ethnic inequalities,” Durán explained. “A civil rights perspective helps us to understand how racism in our society is also embedded in the criminal justice system.”

Sociologists like Durán examine patterns. When particular racial and ethnic groups are overrepresented in incarcerations or shootings by the police, Durán said it’s his job as a sociologist to explain what causes this increased risk to certain groups.

“Although there are institutional efforts, laws, and policies to decrease violations of civil rights by individual actors who enforce laws, we still see ongoing problematic behavior, laws, and policies,” Durán said. “Some people describe discriminatory acts as behavior from ‘bad apples,’ but when we observe higher rates of disproportionate outcomes, we also must be aware of structural problems that continue systemic inequalities.”

King faced and fought inequality that stemmed from both segregation laws in the South and social practices in the North that maintained segregation. Durán said our society still faces racial and criminal justice system inequalities, but modern inequalities aren’t quite as easy to identify as legal segregation.

King faced and fought inequality that stemmed from both segregation laws in the South and social practices in the North that maintained segregation. Durán said our society still faces racial and criminal justice system inequalities, but modern inequalities aren’t quite as easy to identify as legal segregation.

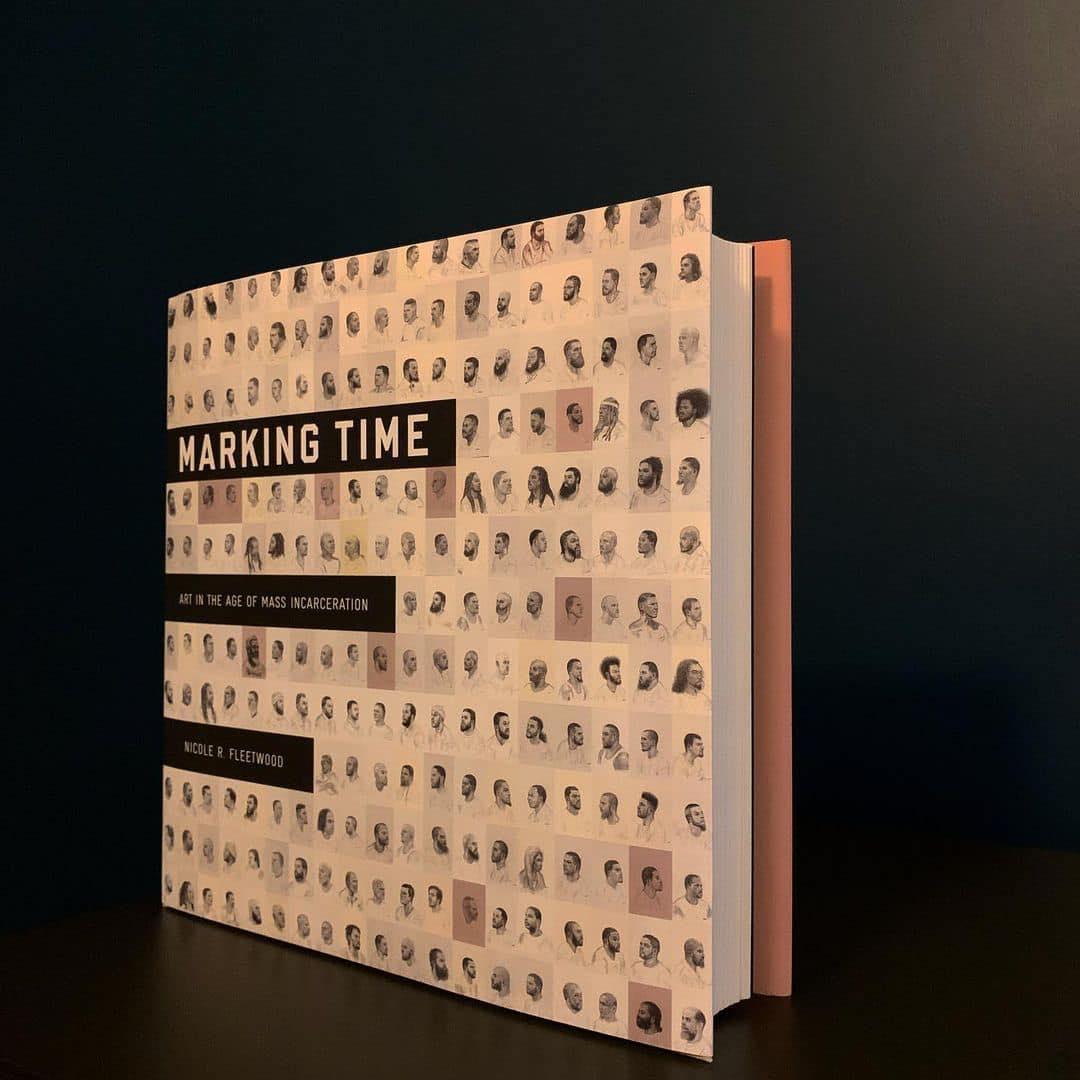

“Incarceration rates do not overlap with crime rates as we have seen a decrease in violent and property crime since the early 1990s,” Durán shared. “Thus, we examine what issues have increased incarceration. The ‘War on Drugs’ is a contemporary issue that has been brought to greater attention with different mandatory minimums such as crack versus cocaine to other forms of enforcement that heightens certain groups in the United States to be arrested, charged, and convicted more frequently than others.”

In Durán’s course titled “Race, Ethnicity, Crime and Justice,” he teaches students about historical and contemporary issues of racial inequality. His curriculum includes the recent court case in which a police officer, who mistakenly drew her handgun instead of her Taser, killed Daunte Wright during a traffic stop in Minnesota. Wright, a 20-year-old Black man, was pulled over for having expired license tabs and a dangling air freshener on the rearview mirror — a minor infraction in his state. It’s a rare case, Durán explained, because the officer was found guilty of manslaughter.

“Officers often describe such traffic stops as ‘looking beyond the stop,’ or focusing not on the infraction but rather using the stop to investigate potential criminal activity,” Durán said. “In this example, the blatant discrimination of targeting certain motorists more than others resulted in a stop for which many people do not get pulled over. The lead officer even stated she would not stop a motorist for this reason. However, legally the officer was able to operate in this manner. The further deterioration of the encounter with Mr. Wright and the officers led to the lead officer firing her gun instead of her taser. The stop and heightened use of force all combined into an experience not equally shared by everyone in U.S. society.”

Following King’s example of advocacy continues to be invaluable to the criminal justice reform movement.

“Grassroots empowerment strategies continue to be key for marginalized communities to bring greater awareness to societal problems,” Durán explained. “Marginalized groups do not have the power or resources themselves to change institutions, laws, or even control the narrative created about social issues by the news media. Increasing public consciousness and advocating for change can help inspire others to get involved and develop a wider array of public support.”

“Grassroots empowerment strategies continue to be key for marginalized communities to bring greater awareness to societal problems,” Durán explained. “Marginalized groups do not have the power or resources themselves to change institutions, laws, or even control the narrative created about social issues by the news media. Increasing public consciousness and advocating for change can help inspire others to get involved and develop a wider array of public support.”

Examples of grassroots efforts making meaningful influences on society’s awareness of criminal justice inequality abound. In addition to ongoing protests since the police killings of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, George Floyd, Botham Jean, Breonna Taylor, and many other Blacks, Latinos, and Native Americans, Durán said grassroots efforts aimed at achieving criminal justice reform have grown.

“We have seen increased involvement from formerly incarcerated individuals working with faith-based organizations and other civic organizations to regain and push for more inclusionary employment and housing policy,” Durán shared. “Marginalized residents have also worked as violence interrupters.”

King said in his “Letter from Birmingham Jail” that human progress is achieved through tireless efforts and persistent work of men. Grassroots efforts in the criminal justice reform movement represent the persistent work required to bring forth justice everywhere by ending injustice in U.S. prisons, jails, and law enforcement practices by following King’s example.

“Education has been a valuable tool to provide greater insight into societal problems and to help guide the creation of solutions,” Durán said. “Dr. King is an excellent example of someone whose leadership and consistent agitation worked to create change.”