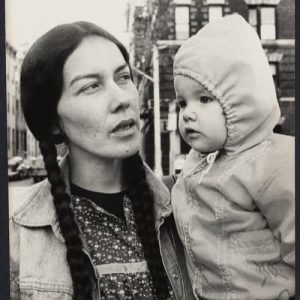

Yvonne Swan, a Colville Native American who lives on the Colville Reservation northwest of Spokane, Washington, found herself in a mother’s nightmare on Aug. 12, 1972.

The day before, Swan’s son was playing outside when William Wesler, a known child molester who lived next door to Swan, grabbed her young son and tried to drag him into his house. Swan’s son managed to break away and ran to his babysitter’s home.

That evening, Swan and her children spent the night at the babysitter’s house. Her sister’s family joined them. Wesler decided to visit the three women and children at the babysitter’s house in the early morning hours of Aug. 12, 1972.

“Moments after Wesler got in the house, he attempted to move toward my 3-year-old nephew who was awakened by the shouting,” Swan recalled. “Wesler moved toward him saying ‘What a cute little boy.’ When my little nephew saw Wesler, he started crying. That’s when my sister moved to shout at Wesler to stay away from her son, and I became afraid for her. She was looking up at him and shouting and he turned toward her and I thought he might hurt her. All I could think of was we were all in danger. I looked for her husband and when I turned, [Wesler] was in front of me and I panicked.”

Swan shot the 6’10” white man.

On Mother’s Day in 1973, Swan was convicted of second-degree felony murder and first-degree assault for killing their attacker. After two appeals, Swan served five years on probation in exchange for a plea deal. Her grueling experience with sexism and racism within the court inspired her to advocate for other women and Native Americans within the court system.

With the help of an all-woman defense team, the Supreme Court ruled that Swan was entitled to have a jury consider her actions in light of her “perceptions of the situation, including those perceptions which were the product of our nation’s long and unfortunate history of sex discrimination.”

“I noticed a certain amount of condescension in the beginning of the trial, and I thought it was due to racism, but as I became acquainted with women of different cultures including feminists, I realized sexism was involved as well,” Swan said. “I later reflected on the verbal and non-verbal cues among a few male lawyers I encountered and I saw it. This broadened my thinking about feminism, and I wondered how condescension began and how it can be overcome.”

As a result of the ruling in her case, the law regarding women and self-defense across the United States changed forever. Swan also worked for the International Indian Treaty Council where she and others brought violations of Indigenous human rights to the world’s attention. She continues to advocate for Native American rights and successfully helped her people get their ancient ancestral remains returned to them and reburied.

“I don’t know when discrimination against women began,” Swan said. “All I know is it’s been used against us for too long, and the general population needs to be enlightened about honor and respect for women on many levels. Having one month each year to globally focus on this education, is a good start to that end. “

Swan was an advocate for women’s rights before the incident with Wesler placed her among pioneers in the second wave of feminism. From a very young age, she was exposed to discrimination on the basis of her and her family’s identities. Her mother was one of her main inspirations for bringing an intersectional view of feminism to light.

“At eight years of age, I witnessed racism against my mother, and it made me angry,” Swan shared. “Racism began with greed for power and riches dating back centuries. Changing that would be a huge undertaking; instead, I tried to get along with people. If they were interested in my culture, I was happy to share and find common ground. My advocacy for other people involved with the courts was the natural thing to do because I empathized. My defense for our land rights came from my mother’s teaching me since my childhood. She was my best mentor.”

Forty-five years after the decision of her landmark court case, Swan said advocating for women’s rights is just as important as it was back then.

“I see it as a matter of life or death,” Swan explained. “If we do not educate the masses that we women deserve respect, nothing will change and babies, girls, women, and grandmothers will continue to be mistreated.”

On March 24 and 25, the Brazos Valley community can hear Swan and two other women of color share their stories of triumph and protest during The Second Wave: Revolutionary Women of Color event, an event hosted by Elizabeth Cobbs.

The Second Wave event will leave attendees inspired to continue making the world a more equitable place for people of all identities.

“If we want positive change, we must become active,” Swan said. “The best way to prepare for that is to arm yourself with cross-cultural knowledge. Unity among humankind has been my greatest wish, and I hope this event will help get us closer to a better understanding and appreciation for our differences and commonalities.”