In early December of 2019, Angela Achorn arrived in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, a city bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and rainforests to the north, east and west. Her research there on macaques – made possible by a Fulbright Research Grant – would comprise the dissertation that would earn her a Ph.D. in anthropology.

After just over a month in the field (“I was just learning my subjects’ names,” she said), news of a respiratory virus spreading through China began to break. Initially she wasn’t too concerned. “I was in the middle of the jungle,” Achorn explained, “and could only get to an internet connection to check emails or read the news every three or four days. This new virus was on my radar, but I didn’t think it would mean I would have to leave.”

Then came guidance from the U.S. State Department for U.S. travelers abroad to return home. The Fulbright program followed with an announcement that they would no longer disburse funds to awardees who ignored State Department guidance. “At first I didn’t understand those decisions,” Achorn said. “I had everything in place: funding, visas, permits. I was collecting data. Besides, I thought it was safer for me to stay in a remote location than to return to cities and travel through airports back to the U.S.”

But staying was no longer an option for reasons an official at the U.S. consulate in Jakarta made clear to her. “I had no assurance against being detained in a foreign country if they closed their borders. And if I had gotten sick or injured, I wouldn’t have been able to get medical attention.”

Finding Her Research Focus

Achorn’s decision to research macaques was the result of years of exploration and a bit of serendipity. As a child, she was drawn to animals, travel and history, but began her undergraduate study at Rhode Island College having yet to find a way to bring these interests together. She entered as an education major planning to be a high school biology teacher.

College, however, provided a series of transformative experiences for Achorn. First, she found anthropology in an archaeology course she took to fulfill a social science credit. “That was the first time I ever really learned what anthropology was,” she said. Next, she found a class on biological anthropology, which she defines as “the study of human ancestors and relatives through time and space,” and changed majors. “Biological anthropology had biology and it had history,” she said. “I fell in love with it.”

Then she got the opportunity to travel to Costa Rica on a research trip with her Rhode Island College faculty advisor, Mary Baker. “I’m so grateful Dr. Baker gave me that opportunity. It was there I realized I could make a career out of traveling to observe primates in their natural habitats to explore questions about evolutionary history. That sealed the deal for me,” she said.

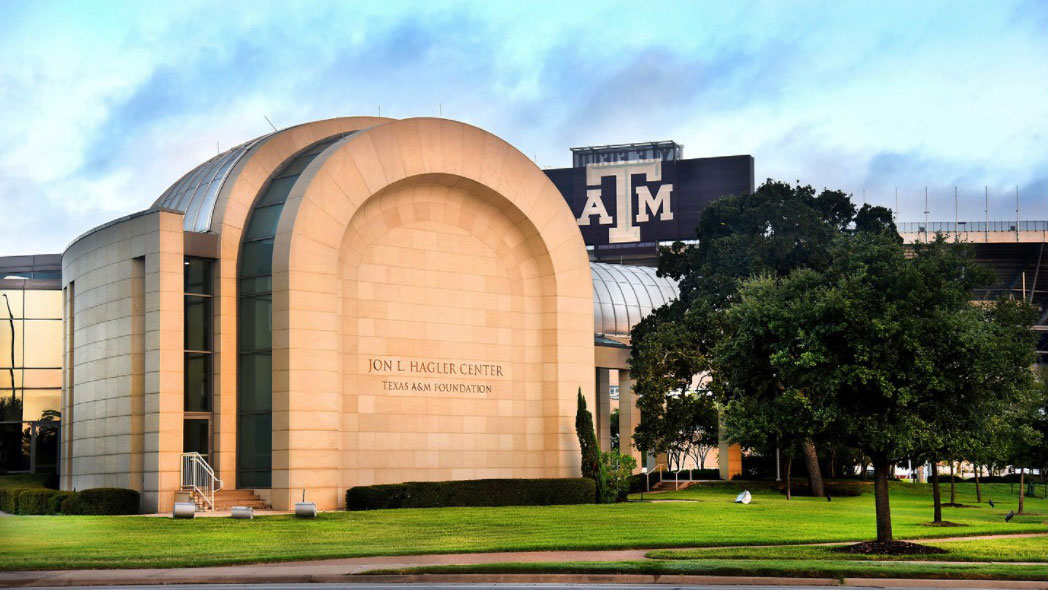

Having earned a B.A. in anthropology, Achorn chose Texas A&M for graduate school for two main reasons. First, she wanted to work under Professor Sharon Gursky, whose research on primates she greatly admired. Second, she liked the design of Texas A&M’s anthropology graduate program, which Achorn says is “truly ‘four field,’” meaning that graduate students do extensive coursework in archaeology, linguistic anthropology, physical anthropology, and cultural anthropology.

“A lot of programs encourage students to be more ‘hyper-specialized,’” Achorn said. “Texas A&M takes a more holistic and well-rounded approach. Even the more focused courses bridge to themes in other fields.”

Initially she intended to do her graduate research on orangutans. But she quickly found that her interests were more theoretical than species-specific. “Once I got to graduate school, I started to develop research questions about cooperation and sociality. Specifically, I became interested in learning about how group size effects disease transmission, how mating behaviors evolve, and how individuals cooperate. Orangutans are more solitary, so I discussed alternatives with Dr. Gursky. She told me that macaques at her field site in Indonesia living in groups of around 100, so I had my species and location.”

Abandoning Her Initial Dissertation Project and Finding a New One

As hard as leaving was to accept, she told herself that she was just losing a month’s work. “I thought it was temporary. I would go home, regroup and refresh my supplies and, in a few months, I would be back.”

But as the months of 2020 crept by and a return trip to Indonesia began to look less likely, she started to hatch a backup plan. “I couldn’t sit idly. While it was discouraging to think about having gotten so far into my macaques project without finishing it, I just kept thinking that I had so many other research interests,” Achorn said. Given the uncertainty surrounding travel, she and Gursky decided the best option would be a project using existing data instead of relying on field research.

Achorn immediately thought of a presentation she had seen at the 2019 Conference of the Texas Association of Biological Anthropologists by Jill Pruetz, Professor of Anthropology at Texas State University. Pruetz’s discussion on how chimpanzees living in savannah habitats made spears to use for hunting appealed to Achorn in a variety of ways.

Like Pruetz, Achorn was interested in chimpanzees and knew that most extant research focused on chimpanzees in rainforest habitats, so studying savannah dwellers could provide new angles of inquiry. Additionally, Achorn thought that a study on humanity’s closest relative from the animal kingdom could shed some light on another of her interests: the evolution of food sharing among human societies. “I kept returning to this question: if they hunted for food, how and why they might share what was too much for them to consume individually and what could their sharing behaviors tell us about sociality?”

Lastly, Achorn recalled that Pruetz had collected a mountain of data in her 15 years observing chimpanzees in Senegal. When Achorn contacted Pruetz about using her data, Pruetz was excited to have Achorn take on the project: “I was thrilled to have Angie dive into an extensive data set that we had started working on but had not yet had the opportunity to finish,” Pruetz said.

Just like that, Achorn had found a new direction for her dissertation.

In her new project, Achorn studied food sharing among Fongoli chimpanzees of southeastern Sénégal. She tested four hypotheses to explain the motivations for food-sharing among Fongoli chimpanzee food sharing patterns: 1) kin selection, 2) generalized reciprocity, 3) sharing under pressure, and 4) food-for-sex trades.

Her findings show that chimpanzees share food for all the reasons she hypothesized. Kinship and reciprocity, however, were the strongest predictors of whether an individual would share with others. Likewise, kinship and reciprocity are the most important factors for food sharing among humans. By illuminating the similarities in patterns of cooperation among humans and chimpanzees, Achorn’s research helps inform our understanding of human cooperation.

Achorn’s dissertation won the admiration of Gursky, who praised her ability to overcome such a dramatic setback in such a short period of time. “Angie had worked hard for four years to plan the macaques project. She had the funding, visas, and permits in place,” Gursky said. “Then, suddenly, she had to drop it all and start over. Few students could have adjusted to a ‘plan b’ with such grace and success.”

Pruetz was equally impressed. “Angie did an amazing job of taking years’ worth of data and testing various hypotheses to explain meat sharing in chimpanzees,” she said. “I am thrilled with her work, and she clearly demonstrated how flexible and creative she is as a scientist, in addition to being astute, intelligent, passionate, and committed to her work!”

Commencement: A Time for Reflection and Looking toward the Future

Achorn believes her life experiences prepared her for the ordeal of starting over on another dissertation project. “I’ve lived in fourteen different cities in ten states,” she said, noting that her six years in College Station is the longest she has ever lived in the same place. “Moving so frequently forced me out of my comfort zone,” she said. “I’m okay with change, even if it involves starting over.”

She fought through disappointment by keeping the end goal – earning the Ph.D. and being able to make a career of what she loves -- in sight. “Being able to research primates combines all the things I’m drawn to,” she said. “I love animals, evolutionary biology, history, and advancing science. Combining these loves into a career is just indescribably wonderful for me.”

After walking the stage at the Texas A&M doctoral hooding ceremony on Saturday, May 7, she will start a position as a post-doctoral researcher at the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, where she will be part of a team researching aging and cognition on non-human primates.

Getting back to researching primates is a fitting turn of events for Achorn after having to abandon field research. “I am ecstatic,” she said. “I’ll be working with primates every single day.”

This story was originally posted on Texas A&M University Graduate and Professional Studies News.