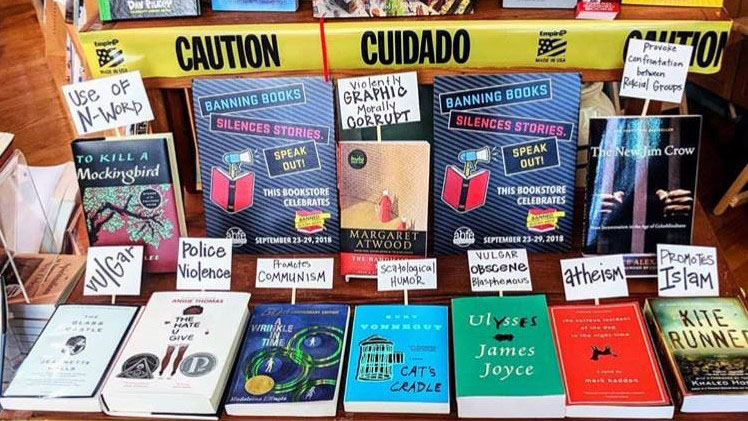

In August, the Keller Independent School District outside of Fort Worth instructed staff to remove more than 40 books from classrooms and school libraries, including Anne Frank’s Diary: The Graphic Adaptation (which was later reinstated). This round of book-banning is the latest in what two reports call an unprecedented wave in U.S. schools. However, according to Texas A&M University scholars in the College of Arts and Sciences, we have seen similar book banning missions play out before.

“Banning books is not new,” said Claire Katz, professor of philosophy, Presidential Professor of Teaching Excellence and interim department head of Teaching, Learning and Culture in the School of Education and Human Development, citing Galileo as one example. “But if we focus only on books, then we lose sight of the root cause of the problem — banning ideas and controlling people’s access to information that allows for critical and independent thought…Totalitarianism proceeds by attacking the outward culture.”

Terri Pantuso, an assistant dean in Arts and Sciences and instructional assistant professor in the Department of English, agreed.

“We’ve had books banned since the establishment of public schools,” she said. “It is troublesome because it robs students of a diverse reading experience and further ties the hands of K-12 educators. Oftentimes books by people of color are banned because they discuss ‘uncomfortable truths…’ Also, books that deal with issues surrounding gender and sexuality are banned, and that is bothersome to me, as children who relate to those issues need to know they are not defective.”

Indeed, the most-banned books in the U.S. today include Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You by Ibram X. Kendi and Jason Reynolds, and George by Alex Gino. The former explores issues related to racism in America; the latter tells the story of a transgender girl named Melissa.

“The content of children’s literature has long been a kind of cultural battlefield,” said Brian Rouleau, associate professor in the Department of History. “Some parents have always sought to engage in gatekeeping and exert control over what their children are exposed to. In the past, during periods of perceived national crisis, parents have often sought to censor their children’s reading for what they argued was the greater good.”

According to Katz, 2021 Minnie Stevens Piper Professor, the potential consequences of banning books are alarming and can include jail or other punishments for those who violate the ban.

“We’ve already seen this in Oklahoma where a teacher lost her job for providing her students the QR code to Brooklyn library books,” she said. “More seriously, when you restrict information, you restrict thinking. This is how totalitarianism proceeds. I really cannot emphasize this enough.”

Rouleau also worries about the quality of education amidst the recent book bans.

“My concern is that all of the hostility directed toward libraries and public schools may drive otherwise qualified and committed people away from those important professions,” he said. “I would imagine that at least part of the problem that school districts are having with staffing has to do with these sorts of controversies.”

Rouleau also pointed out another issue — that parents don’t always agree on what constitutes an objectionable book.

“Sometimes, the protest of one parent can get a book banned from a library’s shelf, when no other parents have a problem with the book in question,” he said. “Parents have a right to act as guardian for their children, but banning a book based upon the feelings of one parent, or even a small handful, so that no other young person can access it may not be the most equitable solution.”

So, what can be done about this latest rise in banning books? As was the case with Anne Frank’s Diary which sparked a heated board meeting, Rouleau suggests getting involved.

“Attend school board meetings, PTA meetings and meetings at other levels of local government that tend to influence these decisions,” Rouleau said. “Run for local elected office. It’s public apathy that tends to let the loudest voices prevail over common sense. Those who are concerned, therefore, need to become involved in local politics and vocal about their points of view.”

Katz agreed.

“Resisting banning, protesting banning, speaking up at school board meetings…these are all things that someone can do,” she said. “Read widely and be aware of what is happening. Support education — especially in the humanities, social sciences and sciences — these are the areas that comprise the books that tend to be banned.”