Mikhail Gorbachev, the final leader of the Soviet Union before its dissolution, has left an indelible impression on history. Whether that’s positive or negative depends on who you talk to. But if you ask Cynthia Werner, an anthropology professor at Texas A&M University and an associate dean for faculty affairs in the College of Arts and Sciences, his leadership changed her life for the better.

Originally from The Woodlands outside of Houston, Werner says she was always fascinated by Russia.

“I grew up during the last few decades of the Cold War, at a time when Russia was regarded as the enemy of the United States,” she said. “I was always curious about the Russian people and thought that there’s no way all Russian people are evil. So as a political science undergrad at Texas Christian University, I decided to minor in Russian. Luckily, this was around the same time Gorbachev was coming into power.”

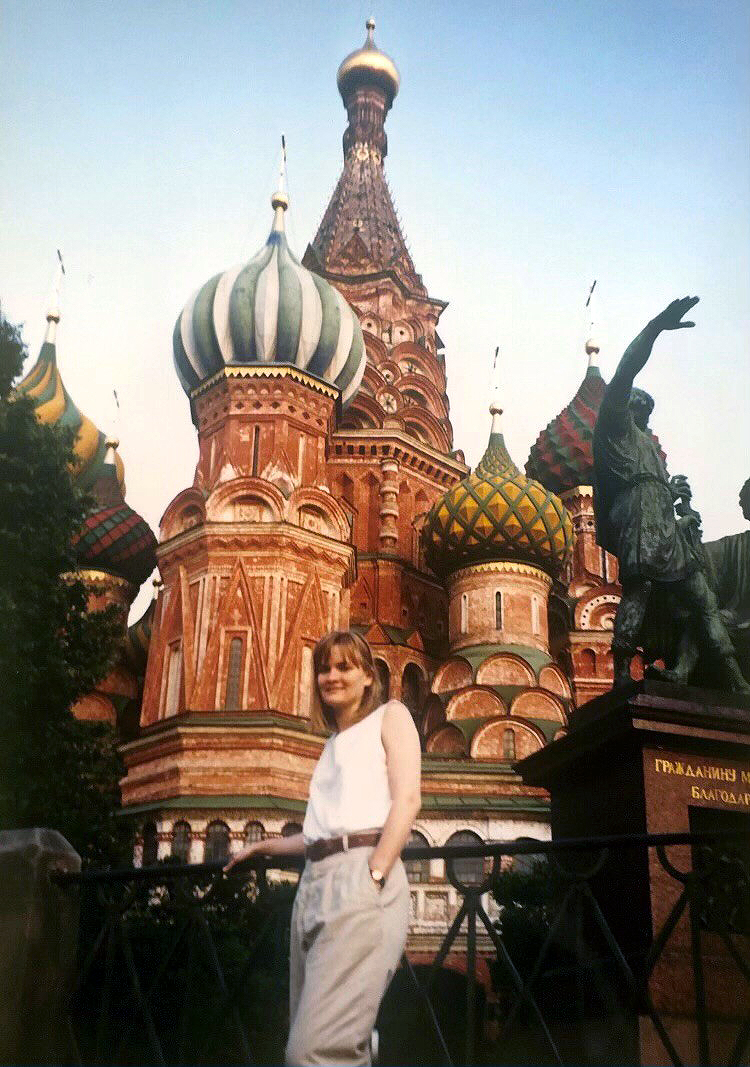

The year was 1987, and Gorbachev had just introduced two of the policies he’s best known for: glasnost and perestroika. It was also the year Werner took a study abroad trip to the Soviet Union, visiting five Soviet republics.

“Glasnost means ‘openness,’ and it led to a critical review of the Soviet past,” Werner said. “Perestroika was the beginning of economic restructuring of the command-administrative economy where the state was in control of everything. At the time, travel to the Soviet Union was very controlled and regulated, and Americans could only go to a limited number of cities and towns. Few people travelled to the non-Russian Soviet republics. Glasnost was still very new, and things were just starting to change. People were just starting to test the boundaries of what they could say and do.”

The next year, Werner found herself working in Washington, D.C. for the nonprofit think tank American Committee on U.S.-Soviet Relations. The organization hosted a visit for Andrei Sakharov.

“Sakharov was known for two things: developing nuclear weapons and then later advocating against the arms race and atmospheric testing,” Werner said. “He was one of the greatest supporters of human rights in the Soviet Union, and he paid a price for this — he was exiled for several decades. It was Gorbachev who freed him from exile shortly before he [Sakharov] came to visit Washington, D.C.”

While Werner’s role in organizing Sakharov’s visit admittedly was a minor one, she is proud to have played a part in that historic event. She said that seeing him speak, which likely would not have happened if not for Gorbachev, further solidified her career trajectory.

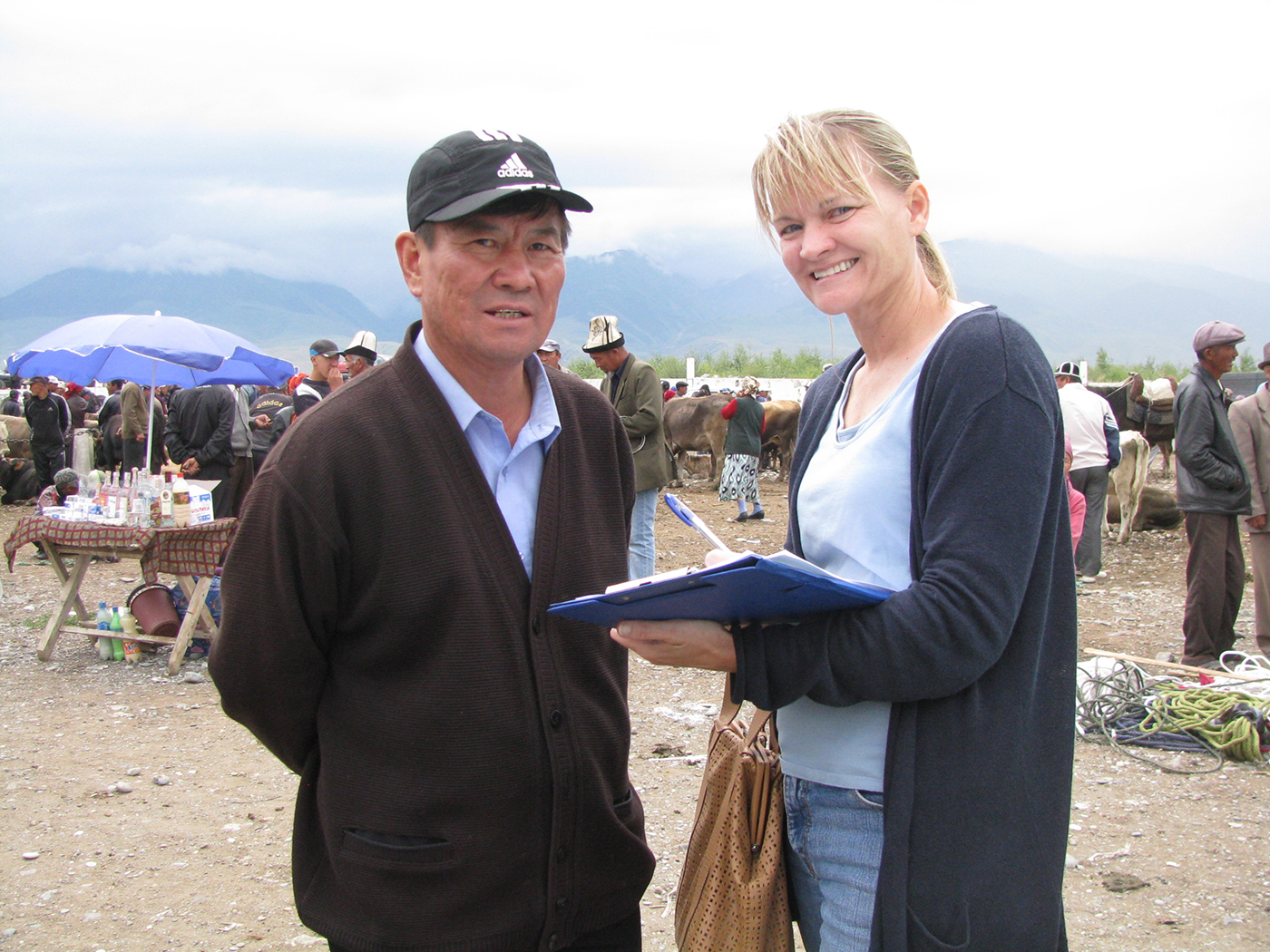

“I was very impressed with his accomplishments,” Werner said. “Later in my career, I worked on a project where I interviewed Kazakh and Russian victims of nuclear testing in Kazakhstan. In a roundabout way, my career was once again intersecting with the lives of both Gorbachev and Sakharov — Gorbachev’s policies ushered in the changes that allowed me to visit a formerly top-secret site where the Soviets tested their first nuclear device designed by Sakharov’s team of researchers.”

Werner graduated from TCU in 1989. In 1990, she began her Ph.D. program at Indiana University, this time studying anthropology.

“I switched in part because everything Gorbachev did led to more opportunities for people to do anthropological research in the former Soviet Union and eastern Europe,” she said. “Anthropologists like to immerse themselves in a community and even live with local people. It was nearly impossible to conduct that type of research in the former Soviet Union before Gorbachev’s rule.”

On December 25, 1991, the Soviet Union collapsed. That day, Gorbachev resigned, leaving Boris Yeltsin as president of the newly independent Russian state. Meanwhile, Werner’s research opportunities were just beginning. In 1992, she started her dissertation fieldwork in Kazakhstan in a small village called Shauildir, where she lived with people she still considers her second family. She has since visited the country more than 10 times.

“Kazakhs were traditionally nomadic pastoralists, living in mobile yurts and raising animals, moving seasonally to allow their animals access to grass and water,” Werner said. “They were forced to settle by Joseph Stalin…The Kazakhs are one of more than a hundred non-Russian ethnic minorities in the former Soviet Union. They speak a Turkic language and identify as Muslim. I found it interesting to study how the Soviet state tried to create a single Soviet identity and change many aspects of their lives.”

Werner believes that the Soviet state initiated some policies that helped perpetuate ethnic identities of minority groups, such as the Kazakhs, while simultaneously pushing other reforms that reduced cultural and linguistic knowledge and, in some cases, forced some groups of people off of their own lands.

“The treatment of Soviet minority groups was not unlike the Native Americans in the United States,” she said.

Living in Kazakhstan for a year and a half in the 1990s gave Werner a bird’s-eye view to the economic and political changes that started under Gorbachev’s rule and expanded after the fall of the Soviet Union. For example, she witnessed the explosion of consumer-good availability in Kazakh villages, as traders started to bring in goods from outside of the former Soviet Union. She also observed how local museums acknowledged past wrongdoings by the Soviet government and how local towns renamed streets after Kazakh heroes who could not be celebrated during Soviet rule.

On August 30, 2022, Gorbachev died in Moscow. In the weeks since, his legacy has been debated among scholars and average citizens alike. For Werner, his legacy boils down to his policy of openness, not just within the Soviet Union, but also with regard to her career.

“In some ways, I can thank Mikhail Gorbachev for creating the pathway for my life and career,” Werner said. “That very first trip to the Soviet Union expanded my horizons and increased my awareness of cultural differences. At the same time, Gorbachev’s reforms brought changes that made it possible for me to go live in a rural community and conduct ethnographic research in the middle of Central Asia. I don’t think those opportunities would have been possible without Gorbachev. He was trying to open up the Soviet Union to the West, but in so doing, he opened up the door to people like me.”

Learn more about Werner and her research, which has been funded in part by the National Research Council, American Association for the Advancement of Science, National Science Foundation and National Council for Eurasian and East European Research.