In 1906, a new carol appeared in “The English Hymnal,” an influential collection of British church music. With words by British poet Christina Rossetti, set to a tune by composer Gustav Holst, it became one of Britain’s most beloved Christmas songs. Now known as “In the Bleak Midwinter,” it was voted the “greatest carol of all time” in a 2008 BBC survey of choral experts.

“In the Bleak Midwinter” began life as a poem, which Rossetti simply titled “A Christmas Carol.” When the hymnal paired her words with music, the poem took on a new identity in song — a phenomenon documented by literature researcher Emily McConkey. But it also became embedded into popular culture in nonmusical forms. “A Christmas Carol,” or parts of it, has appeared on Christmas cards, ornaments, tea towels*, mugs and other household items. It has inspired mystery novels and, more recently, became a recurring motif in the British television series “Peaky Blinders.”

As a scholar of Rossetti, I’ve long been fascinated by the afterlife of her poems in music. The Christina Rossetti in Music project, a database of musical adaptations that incorporates my work, now lists 185 versions of “In the Bleak Midwinter.”

But before it could be set to music, “A Christmas Carol” had to make its way into print as a poem — and that wasn’t so easy. Though written by one of Britain’s mostly highly regarded poets, the poem failed to make its mark on British readers until Holst set it to music. Instead, it found its first, and most enthusiastic, audience in the United States.

Victorian Music

“A Christmas Carol” circulated during a carol revival in the United Kingdom. In December 1867, shortly before Rossetti started offering her poem to British magazine publishers, the century’s most influential collection of carols was published.

Previously considered a folk tradition — and not considered fit for worship, given the revelry they were associated with and the mix of sacred and secular lyrics — carols were coming into vogue. And increasingly, they were finding their way into church.

At a time when women could not be ordained as preachers, writing carols and more formal hymns was a rare opportunity for women to shape the church. Barred from the pulpit themselves, female writers spoke from the pews, including Sarah Flower Adams — she wrote “Nearer, my God, to Thee” — and Cecil Frances Alexander, author of the beloved carol “Once in Royal David’s City.”

Rossetti, a devout Anglican and the author of a number of devotional poems, was among them. Although 21st-century readers may know her primarily through her poem “Goblin Market,” Rossetti’s religious poetry was well known to her contemporaries. By the 1870s, several of her poems had been reprinted in British religious anthologies and hymnals.

A Bleak Beginning

“A Christmas Carol” opens with a vivid description of the harsh physical and spiritual landscape into which Jesus was born:

In the bleak mid-winter,

Frosty wind made moan;

Earth stood hard as iron,

Water like a stone

But it failed to impress George Grove, the new editor of Macmillan’s Magazine at the time. According to scholar Simon Humphries, in 1868 Rossetti sent “A Christmas Carol” to the British magazine, which had previously published her poetry. In what might now be regarded as one of the worst editorial decisions of the century, Grove rejected her submission.

Rossetti eventually placed “A Christmas Carol” in another British journal, The People’s Magazine, in December 1873. But as luck would have it, that was the very last issue, and the poem was relegated to half a page, sandwiched between an essay on “The Life and Habits of Wild Animals” and a now-forgotten poem titled “The Red Cross Knight.” “A Christmas Carol” was all but ignored in the U.K. for over a decade.

The American Reception

Meanwhile, a very different scenario was playing out in the U.S. In November 1871, Scribner’s Monthly dropped a hint about its Christmas issue, which would include a “little poem … sweet and clear and musical.” “A Christmas Carol” debuted two months later.

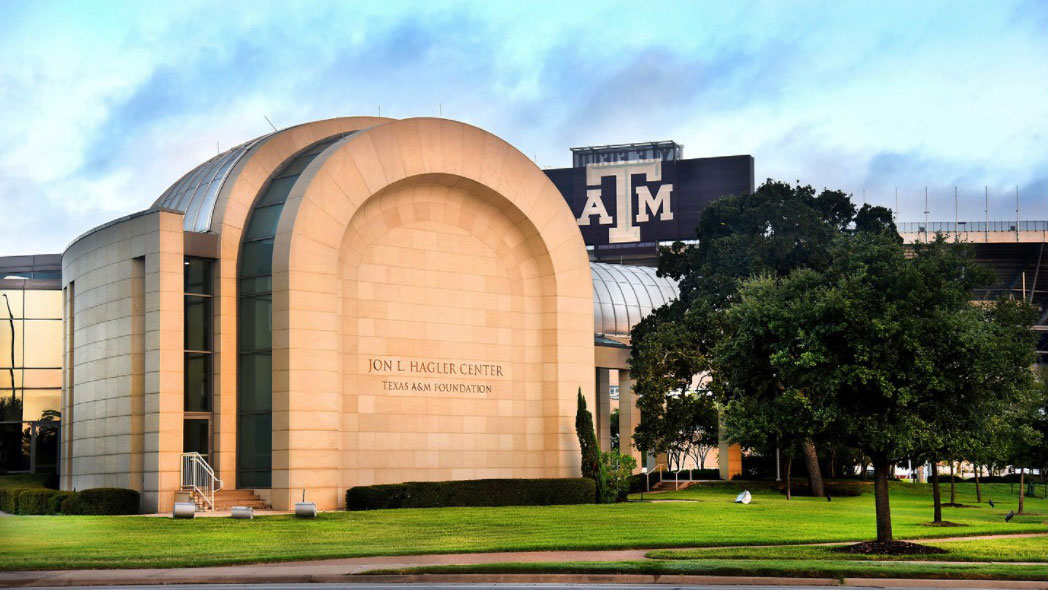

Founded in 1870, Scribner’s Monthly sought to publish “the best authors,” making their work accessible and attractive to a mass audience through illustrations. The magazine paired Rossetti’s poem with a striking half-page illustration of the nativity by the well-known British illustrator John Leighton.

Scribner’s dramatic presentation of Rossetti’s poem ensured that it would be noticed. It was reprinted in anthologies and newspapers, ultimately making The New York Times on Dec. 25, 1892.

The first mass merchandising of Rossetti’s poem also occurred in America. In 1880, an artist named Anne Morse incorporated its first and last stanzas into her prize-winning design for a Christmas card contest held by publisher Louis Prang, who popularized the tradition of sending Christmas cards in the U.S. The company published Morse’s card, distributing Rossetti’s words to homes across the country.

A Mystery Solved

By the mid-1880s, however, “A Christmas Carol” was finally gaining traction in Britain. In 1885, it was included in a holiday-themed anthology titled “A Christmas Garland.” The Illustrated London News named Rosetti’s poem the best modern carol in the collection. Even more visibility came when “A Christmas Carol” was chosen for a collection of religious poetry compiled by influential editor Francis Palgrave in 1889.

In 2006, I discovered a letter in which Rossetti claimed not to have known about Scribner’s publication of “A Christmas Carol:” “I do not know how it happened,” she wrote, remembering only that the poem had come out in The People’s Magazine. At the time, I was unable to locate “A Christmas Carol” in The People’s Magazine, and assumed Rossetti’s memory was faulty. It wasn’t, as the long-sought copy of the 1873 issue now perched on my desk proves.

But Rossetti’s forgetting about Scribner’s Monthly — unaware of the role it played in bringing her work to American readers, and ultimately British ones too — is perhaps the strangest twist in the story of the “little poem” that, unbeknownst to her, would become her most popular work.

* This link is no longer active and has been removed.

This story was originally published by The Conversation.