Hoi-eun Kim, an associate professor in the Department of History at Texas A&M University, has received a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) to complete a manuscript describing the lives and perspectives of Japanese doctors during Japan’s 20th century colonization of Korea.

“Korea is now an independent country divided between North and South,” Kim said. “But before it was divided, from 1910 to 1945, Japan made Korea a settler colony. Over the course of those 35 years, hundreds of thousands of Japanese actually moved over to Korea. By 1945, there were about 800,000 Japanese living there.”

According to Kim, who grew up in South Korea, the influx of Japanese necessitated a military presence, a police presence and bureaucrats to support their expatriate society and help to control the Korean population.

“The whole idea of colonialism was predicated on the notion that these are ‘primitive’ people and that we, the people of ‘civilization,’ need to go and help them,” Kim said. “From 1910 to 1919, Korea existed in what’s called ‘military rule.’ Education was mostly conducted in Japanese, and by the 1940s Koreans were being forced to take up a Japanese name. These were all ways to assimilate Koreans into Japanese.”

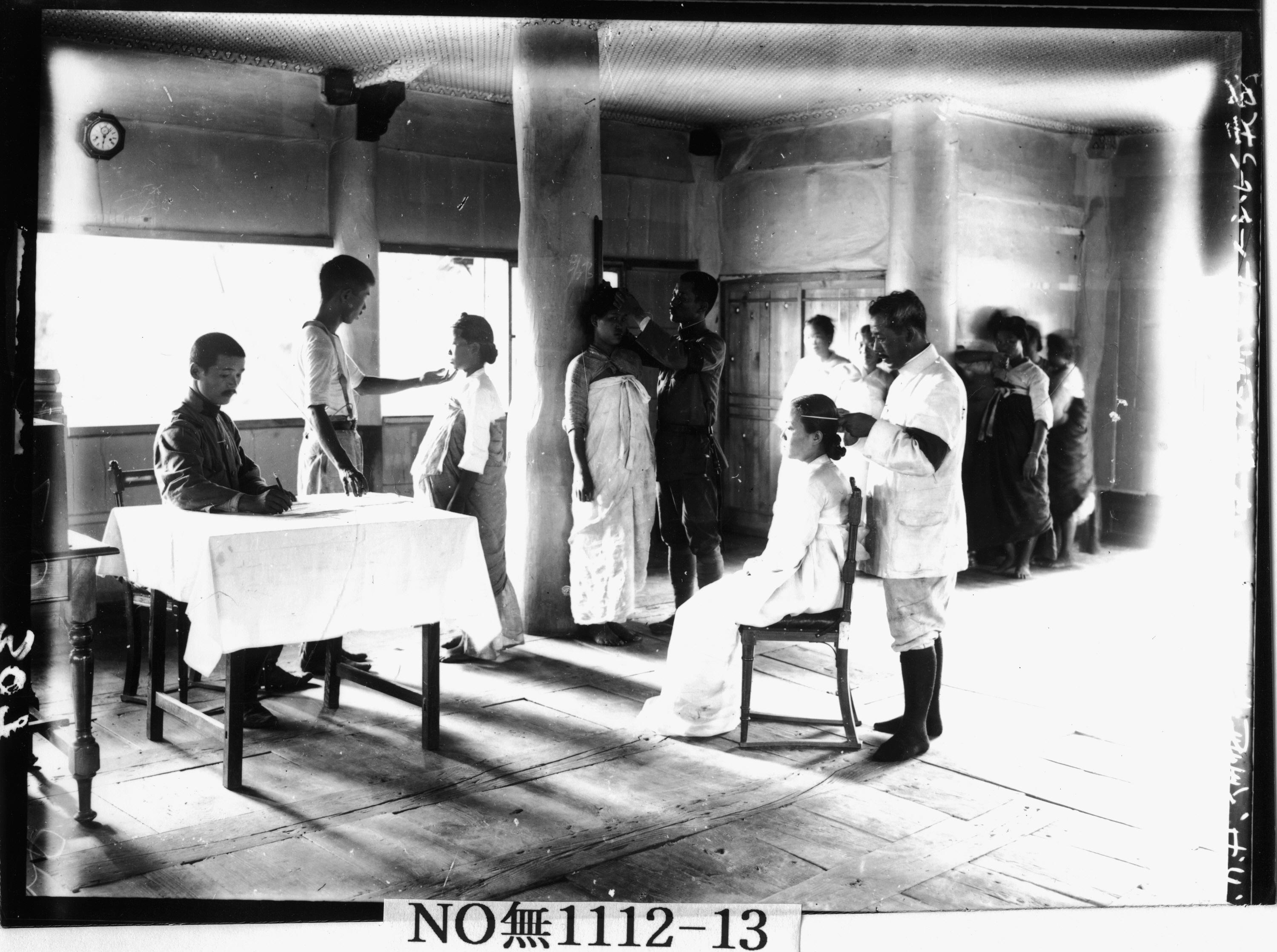

Hand in hand with assimilation, Kim said Korea needed medical doctors, not only to ensure the physical safety of the Japanese people but also to train Korean doctors. However, another purpose of these doctors was to prove that scientifically, Koreans were “inferior” to the Japanese.

“These doctors, or imperial collaborators, were providing information, such as anatomical studies of Koreans as a race,” Kim said. “One of the unique things about Japanese colonization of Korea as opposed to American colonization of the Philippines or the British colonization of India is that there’s no racial distinction at skin level. But the Japanese needed doctors to identify and create these racial differences to justify colonial rule, which by definition assumes differences in racial hierarchy.”

Kim notes that, by the early 20th century, doctors became professionalized across the world. Japan was eager to modernize and embraced Western medicine.

“Before that, there were all kinds of self-licensed people who could claim to be doctors or healers,” he said. “When medicine became professionalized, doctors began to create their own organizations and associations.”

To separate the legitimate doctors from the rest, Japanese physicians published medical directories with the names, affiliations and education of accredited doctors. These directories served as crucial primary sources for Kim’s research.

“I use what historians call prosopography, or the collective biography, meaning that I’m looking at the entire group of people, not just hand-selecting a few,” he said. “Other studies were only focusing on a handful of people who may fit the stereotypical image of colonial doctors, presenting them as pawns of imperialism.”

Kim believes previous studies have failed to look at the complexities of Japanese doctors.

“My goal is to draw a nuanced picture,” Kim said. “There were many other reasons Japanese doctors worked in Korea, including the fact that doctors had become the most mobile profession, as medicine had become universal. And the fact that Japan is so close to Korea, and doctors were able to go back and forth.”

Kim said he looks at the doctors in three groups: private practitioners who wanted to make financial gain, indulging in what historians call “medical capitalism;” educators who trained Korean doctors; and the imperial collaborators.

“To make things more challenging, many of these Japanese doctors and their students wrote their medical articles and dissertations in German, because German was the globally recognized language of science and medicine,” Kim said. “If you wanted to go to medical school in Japan in early Meiji period (1868-1912), you would need to learn German, because all instructions were in German.”

Kim says this makes him uniquely qualified to conduct this research, as his background is in German history.

“I’m ethnically Korean, was educated in German history, and I spent three years in Japan,” he said. “I’m at the crossroads of these three different fields and language capabilities.”

Kim said he is thankful to the College of Arts and Sciences for assisting him in receiving this grant.

“To get a competitive grant like NEH, a lot of preparatory work has to be involved and, in that regard, I can say that the support from the college was critical,” he said.