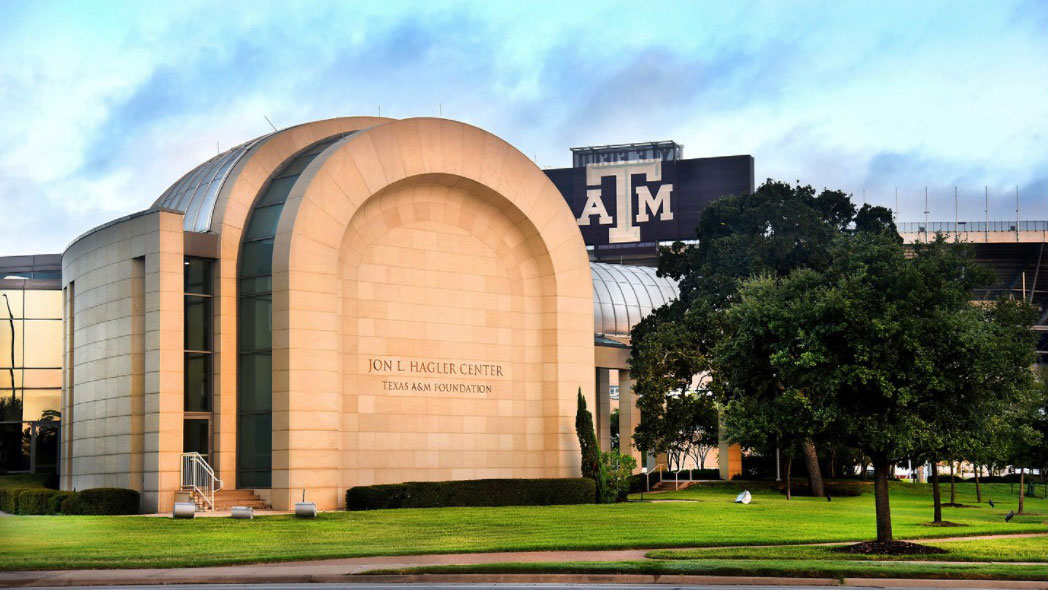

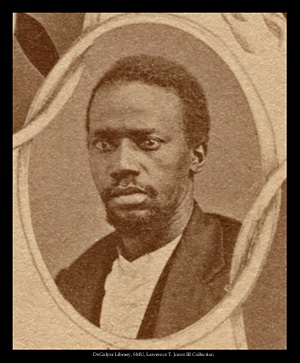

At the heart of Texas A&M University, a statue of Sen. Matthew Gaines stands defiant, one arm outstretched, the other cradling a law book and a Bible. From its pedestal near the Memorial Student Center, the sculpture’s eyes gaze southwest, toward the Brazos River and the vast stretches of agricultural land beyond.

About 50 miles in that direction, in one of the many unmarked graves dotting the landscape of nearby Lee County, Gaines’ physical remains lie buried and forgotten, their exact location lost to time.

“We really want to find his grave,” said Gaines’ great granddaughter Marilyn Alexander-Walls. “Back then, people didn’t always mark graves well, and they didn’t keep a whole lot of documents. The only thing we know is that he was buried somewhere around Giddings,” the small community where the former legislator lived out his later years.

In some ways, this anonymous final resting place is emblematic of the way Gaines and his story were treated in the years following his death. Even toward the end of his life, the man once known throughout the region as an impassioned preacher, statesman and civil rights activist was already fading into obscurity. Eventually, his name all-but-disappeared from both the historical record and popular memory.

It would take decades of hard work to bring it back.

“History has kind of rediscovered him here in the late 20th century and early 21st century,” said Carlos Blanton, professor and head of the Department of History at Texas A&M.

While the November 2021 statue unveiling was a significant and widely-celebrated milestone, Blanton says there is still plenty of work to be done: “I suspect we’ll probably know even more about Matthew Gaines in the years to come.”

Still, it’s worth asking why Gaines was forgotten in the first place. Ultimately, Blanton said, his story illustrates how the lives and contributions of Black Texans have been intentionally and systemically erased — and how bringing that history back to life is both difficult and necessary.

‘A Bad Slave’

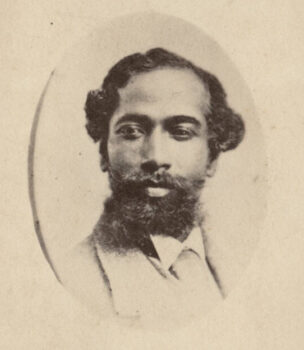

Details about Gaines’ early life are scant. In the absence of any formal diaries or memoirs, historians have relied on statements Gaines gave to the press and stories he shared with his wife and children to construct a rough timeline of his life while enslaved.

“Any reading of those sparse details of Matthew Gaines’ life really shows you the grittiness of that world,” Blanton said. “The denial of basic rights of human freedom and human liberty simply did not sit well with some, and the things that made Matthew Gaines a ‘bad slave’ (his defiance of authority and constant struggle to be free) actually made him this wonderful person who was able to become a leader after the era of slavery ended.”

Gaines was born around 1840 on a Louisiana plantation. 1850 census records mention one 39-year-old female slave and six enslaved children living on the small estate in Rapides Parish — presumably Gaines, his siblings and their mother. The identity of his father is unknown.

On some evenings, a young Gaines would sneak off into a corn field, where he taught himself to read by candlelight. Gaines would later state that he had an accomplice in this endeavor: a white boy who lived on the plantation and agreed to sneak him some books.

“It’s evident that he had a real zest for learning,” Alexander-Walls said. “But more than that, he had a zest for people being able to be treated fairly.”

Perhaps it’s not surprising, then, that Gaines used his literacy and strong sense of moral justice to begin preaching the gospel to his fellow slaves. His early commitment to ministry is highlighted by historians Alwyn Barr and Robert Calvert in their 1981 book “Black Leaders: Texans for Their Times.”

“(Gaines) often told his wife and children, much to their amusement, of disguising himself as a woman — replete with dress and sunbonnet — so that he could drive a buckboard (a type of small horse cart) to nearby plantations to preach, without being stopped by the patrollers,” Barr and Calvert wrote.

Over the years, Gaines made at least two semi-successful escape attempts.

The first came shortly after the death of the Louisiana plantation owner, at which time he was sold in the New Orleans slave market and sent to work on a steamboat. Within a few months, Gaines was on the run, traveling hundreds of miles north into Arkansas. In a move that has puzzled historians, he appears to have remained there only six months before returning to New Orleans, where he was recognized and apprehended.

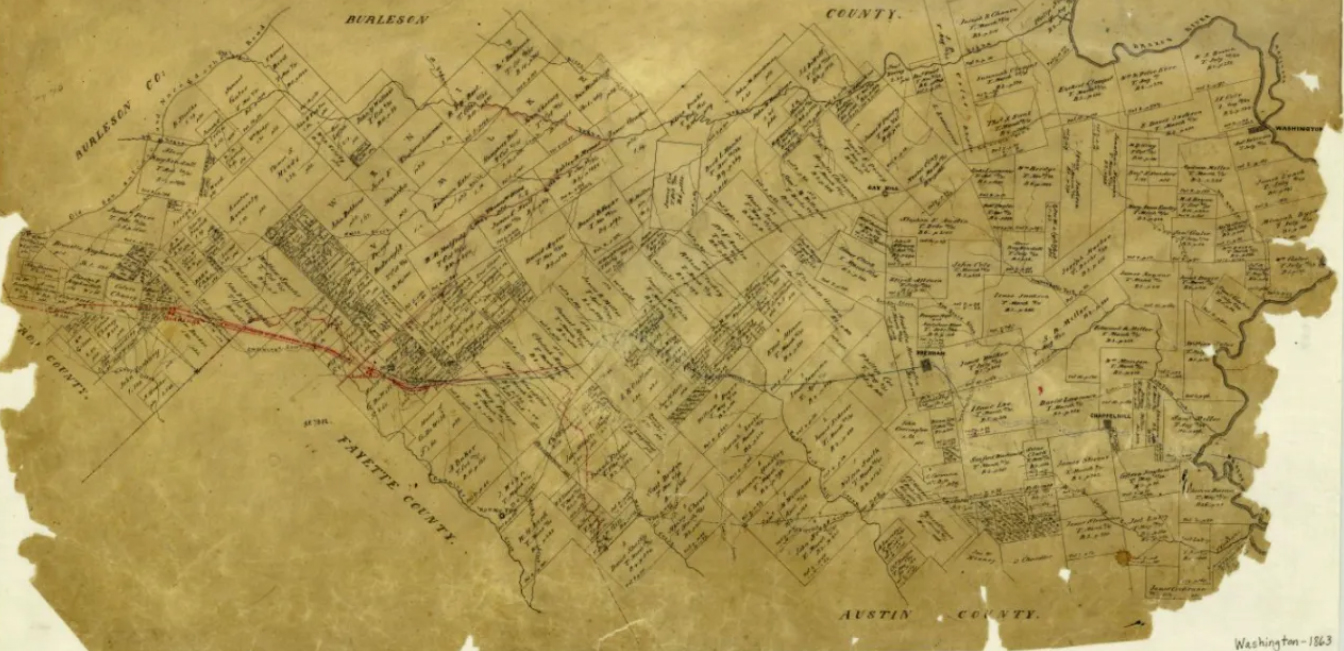

In 1859, Gaines was brought to Texas and sold to Christopher Columbus Hearne. The wealthy Hearne family owned 10,000 acres of fertile Brazos River bottomland, which they used to grow cotton. Gaines was a slave on one of their plantations in Robertson County until 1863, when he decided to run away to Mexico.

“He took every chance he could possibly get, particularly in Texas, knowing that there is an international border and a foreign nation that had, at worst, an ambivalent and, at best, a slightly liberationist view towards escaped slaves,” Blanton said.

Though he never made it to the border — he was captured by a group of Texas Rangers near Fort McKavett — this second escape attempt was not a total loss for Gaines. Rather than being returned to the plantation, he was held in Fredericksburg until the end of the Civil War.

“Although ostensibly still a slave and under arrest, Gaines had considerable freedom of movement and worked as a blacksmith and a sheepherder,” Barr and Calvert note.

Finally, in the summer of 1865, Texans received a piece of news that threatened to upend the social and political fabric of the entire state, setting Gaines on a collision course with the State Capitol.

‘On The War Path’

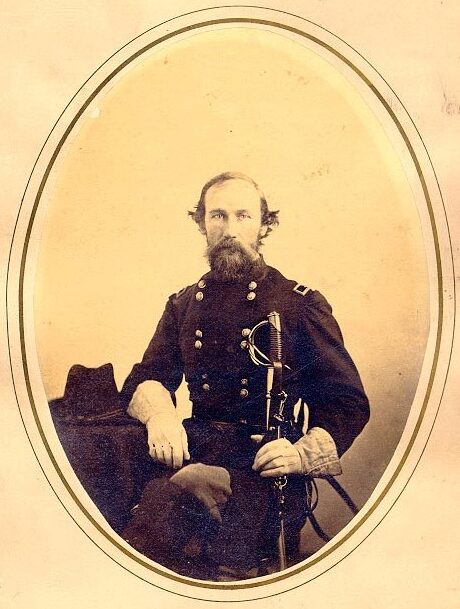

When Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger sailed into Galveston harbor on June 19, 1865, his mission was one of both liberation and control.

As Texas A&M professor of African American history Albert Broussard explains, Granger’s famous statement informing enslaved Texans of their freedom also outlined the limits of that freedom.

“It’s a very peculiar kind of statement,” Broussard said. “They’re expected to remain with their employers, but now the relationship is employer-to-employee as opposed to enslaved person-to-master. No idleness will be tolerated. They don’t want them roaming the roads, even though they may be looking for family members, children or loved ones.”

It was during those strange early days of emancipation that Gaines decided to make his return to the Brazos Valley. Still a young man in his 20s, he settled in the small, predominantly Black community of Burton in Washington County, where he began to preach.

“This is a period when Black people are trying to understand the meaning of freedom,” Broussard said. “And that’s a difficult question because whites come back from the Civil War angry and unrepentant. They do accept the end of slavery, but they don’t necessarily accept the idea that Black people are equal to whites.”

It was in this highly charged environment of Reconstruction that Gaines began his career as an activist and politician. According to Barr and Calvert, the earliest mention of his activities in this arena was an 1869 news article in the Houston Union about that year’s elections: “Davis will carry the county easy,” the paper’s Brenham correspondent wrote. “We have Matt Gaines on the war path, and he is doing good work.”

“Davis” referred to the former Union general Edmund J. Davis, whose victory in the governor’s race ushered in a period of political dominance for the Radical Republican faction, to which Gaines and other Black politicians were aligned.

“The Republican Party under Lincoln was the party to free the slaves and so black leaders, of course, believe that’s the only party that’s going to protect their interests and protect their lives,” Broussard said. “And even before the 15th Amendment, Black men are voting.”

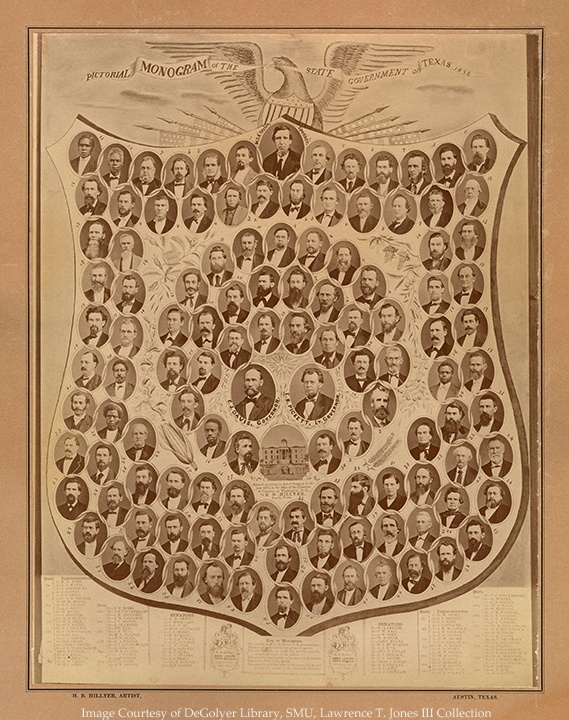

In Texas, this powerful new bloc mobilized to sweep the state’s first group of Black legislators into office. Gaines was one of two Black men to hold a seat in the Texas Senate during the 12th Legislature, along with a handful of others elected to the state’s House of Representatives.

The historical significance of the moment was not lost on Gaines, who later remarked that “the old state of affairs has died out.”

‘They May Kill Me’

If Gaines and his compatriots had indeed put an end to the old state of affairs, it is clear from his actions in the legislature that he was intent on ensuring it was well and truly dead.

In speeches on the Senate floor, he railed against the old evils of slavery and the new evils of voter suppression, violence and intimidation carried out by groups like the Ku Klux Klan. Not satisfied with mere emancipation, Gaines consistently agitated for true freedom and equality for his fellow Black Texans.

“We are legislating for the people of this State, under this new condition of affairs. The old corruption of the Confederacy was buried at the surrender of General Lee,” Gaines proclaimed. This particular speech was in support of a measure to combat the Klan and other violent groups by forming a state militia. “And if the Ku-Klux don’t get me,” Gaines said, “perhaps by the time my six years in this Senate expires, I may be able to go to Congress.”

He spoke at length of the tremendous possibilities ushered in by the new Radical Republican government. For Gaines and the other Black statesmen of the era, this was a chance to stand up to the old majority of Texans who, in his words, “could not recognize the fact of a man of my color being equal with them before the law, or one of my complexion having the right to the ballot box, and the right to enter a school house.”

Education was an issue particularly close to Gaines’ heart. He and his fellow Black legislators unanimously supported the 1871 measure allowing Texas to establish its first public institutions of higher education — the all-white Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas (now Texas A&M) and a separate institution for Black students which later became Prairie View A&M.

His commitment to public education can be seen elsewhere too. When the legislature moved to establish free public schools for all Texas children, Gaines was strongly in favor. He was also adamant in his stance that these institutions should never be segregated, at one point saying to Black parents, “send your children to any of the free schools you want to.”

“They talk about separating them,” Gaines said. “It can’t be done. They are of all shades of color, and there is no dividing line, and my children have the right to sit by the best man’s daughter in the land. And if they ain’t together in the day, they will run together at night.”

It was comments like this, along with his militant approach to political organizing and his willingness to criticize even his fellow Radical Republicans, that made Gaines a target of considerable backlash.

“I have heard that the Democrats have threatened to kill me,” Gaines once said to a crowd of over 3,000 in Brenham. “They may kill me, but I pray that if they do that you who are present today will take sevenfold vengeance for me.”

Ultimately, his enemies chose a different angle of attack. Faced with Gaines’ overwhelming popularity among the Black residents of his district, they chose to use the legal system to disqualify him from holding office.

In 1871, Gaines was indicted on trumped up charges of bigamy. Though it was true that he married his second wife without annulling his first marriage, he did so only because the first ceremony had been performed illegally and was thus considered invalid. Despite testimony revealing as much, Gaines was convicted, jailed and later denied his seat in the 13th Legislature. The fact that his conviction had already been reversed by the Texas Supreme Court was disregarded.

Blanton said the ousting of Gaines was a sign of things to come. As the project of Reconstruction was gradually abandoned, former Confederates returned to power and worked to claw back much of the progress that had been made.

“You really began to see this coordinated effort to do away not just with the Republican Party as it then stood, but to do away with the ideas they stood for: free education, a public school system, civil rights for African Americans, and the existence of a state police force that would actually enforce laws across county jurisdictions,” Blanton said.

Efforts to prevent Black people from voting and holding public office became increasingly successful, and the political environment that had empowered figures like Gaines ceased to exist.

Looking back more than a century later, Texas A&M history professor Dale Baum would remark in a speech to A&M’s Black Graduate Student Association that “Texas A&M and Prairie View A&M are today the only two tangible achievements of the bi-racial democracy which was briefly brought to power in Texas by Black political activism in the late 1860s and early 1870s.”

‘A Long Time’

For Gaines’ part, he continued to fight for equal treatment. In 1875, he was arrested for giving a civil rights speech in his new hometown of Giddings.

After that, reports of the former senator’s activities became less and less frequent. By the time he was buried in 1900, his name was already disappearing from history, as the reactionary forces that had reclaimed control of the state worked to bury the stories and contributions of Black Texans.

“The legacy of Matthew Gaines was, I think, intentionally and willfully forgotten by generations of Texans,” Blanton said. “There’s a whole generation or two of historians who simply did not know, or would not repeat what they knew, about those African American state legislators — not just Matthew Gaines, but others as well.”

Gaines’ story could have ended there. And for a time, it did. But as Blanton notes, “just because something is forgotten doesn’t mean it can’t be remembered.” Even before Gaines himself was rediscovered, many of his favored policies started to get a second look.

“A lot of those ideas in the 1870s that came out of Reconstruction, they worked,” Blanton said. “They just had to be brought back to life decades later, when even reactionary Texans had to admit that things like public schools were a good thing.”

Later on, the Civil Rights movements of the 1950s and 60s ushered in a renewed interest in preserving and teaching Black history. Soon, historians across the country were rushing to recapture the stories of earlier Black Americans before they faded entirely.

“When people die, they take so much unshared history with them,” Alexander-Walls said. “Our traditions are heavily based on oral history, so when those people die and nobody’s writing it down, it takes resources and time to really research things.”

When historians Barr and Calvert visited Giddings in the 1970s, residents could still recount stories of “Old Man Gaines,” the kind, charismatic preacher and community leader who helped establish a local Baptist church.

Some told of Gaines’ rumored ability to “pray down the rain,” or the lengthy speeches he would deliver each Juneteenth on the banks of the Brazos River, “always ending with the assurance that in the eyes of God, black men and women were as good and well-loved as any white, (and) exhorting them to hold up their heads with pride, even in troubled times.”

At Texas A&M, Baum and others started working to illuminate Gaines’ role as one of the university’s earliest founding fathers. Today, thanks to decades of work by historians, writers, activists and family members, Gaines’ contributions have been brought into even sharper focus.

When the statue of Gaines at A&M was unveiled in 2021, Alexander-Walls was in attendance along with her 80-year-old sister Sharon and about 50 other relatives. “For this to happen in her lifetime is something we’re all ecstatic about,” Alexander-Walls said.

And while there’s plenty more work to be done — like the daunting task of locating Gaines’ grave — Sharon Alexander says she’s proud to see that her great grandfather’s name and legacy are no longer just a footnote.

“It’s taken a long time,” she said. “But some people have been fighting for it for a long time.”

This story was originally published by Texas A&M Today.