As Labor Day approaches and the Hollywood writers’ strike continues into its fourth month, Texas A&M University Professor of Communication Dr. George Allen O. Villanueva provides historical context for the current dispute.

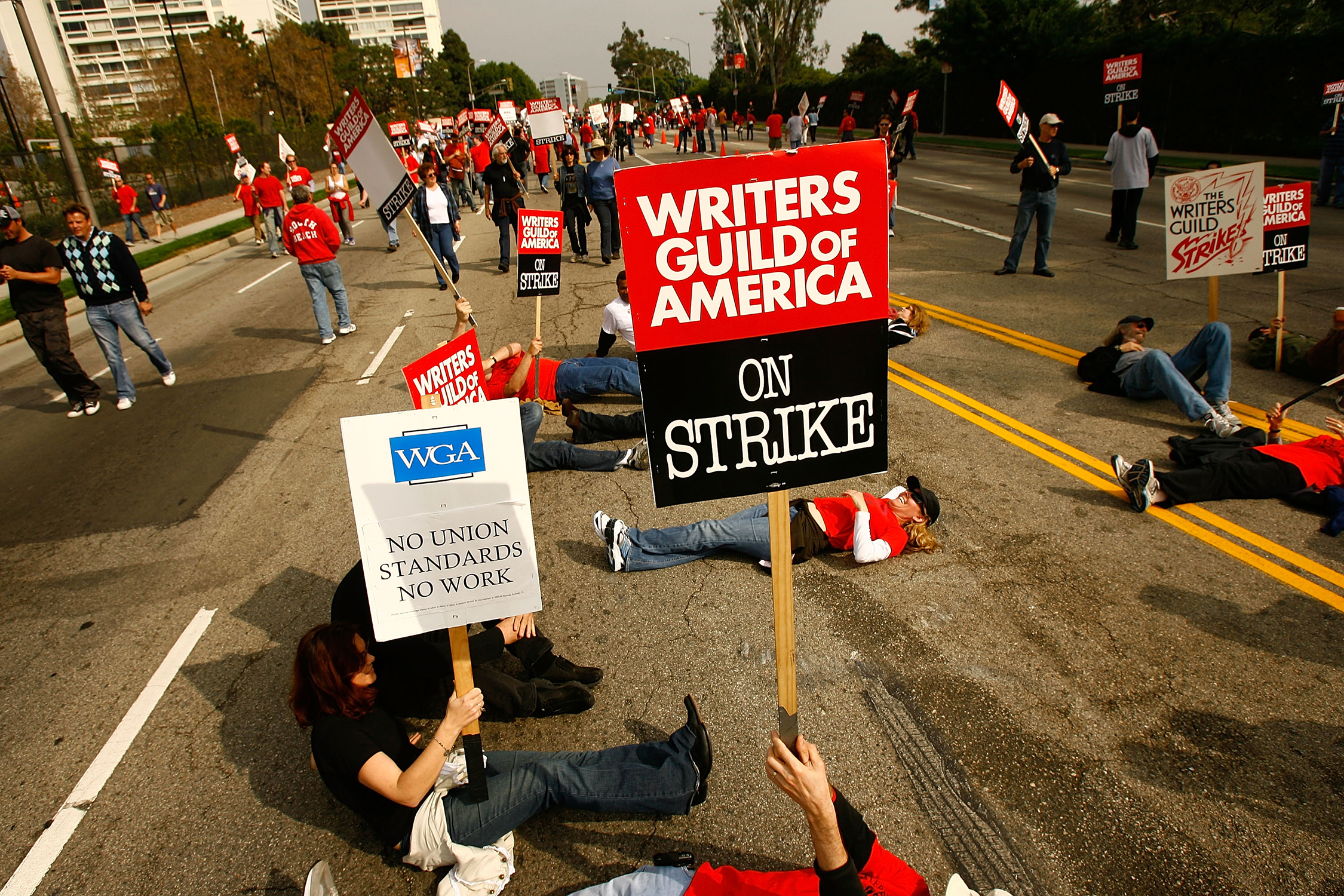

The Writers Guild of America (WGA) began their strike on May 2 over a labor dispute with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP). The Screen Actors Guild–American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA) followed suit on July 14, forming a “double strike” of actors and writers unseen since the 1960 WGA and SAG strikes that resulted in changes in labor compensation for both parties, such as through improved rights, residuals, pensions and net income.

What makes a union unique versus other political and/or social organizing models?

What makes a union unique is that workers pay dues to become members. The workers are of a particular field, in this case being the writers and actors, but others include the famous unions of truck drivers across the country or electric workers, health workers or hotel workers.

A second thing to consider are the political stakes at hand. Members defining themselves as workers is important because it defines them against the actual ownership class and the people who are typically defined as the CEOs or the corporate administration. There are political stakes from having a class consciousness that clearly identifies the ownership class and the leaders as the people who should be making decisions that make a fairer working environment.

What are common reasons for groups to engage in strikes? What makes a strike a unique political tactic?

Strikes are often seen as one of the last-ditch efforts in the American popular consciousness because it is a work stoppage. A work stoppage not only puts people and their families in potential harm’s way because there aren’t going to be any paychecks coming in but also threatens the ownership class in respect to their product, the work being done and their profit margin. Historically in the United States, we’ve seen this happen particularly in cities that are blue-collar or working class. For example, there is Chicago and the Haymarket strike near the Fulton-Randolph markets at the turn of the century that advocated for an 8-hour workday so that ownership classes wouldn’t expect people to work more than eight a day without getting fairly compensated. Chicago’s Haymarket strike eventually led to the recognition of May 1 as international Labor Day in industrial nations worldwide and the current U.S.-legislated Labor Day in September.

Strikes are unique modes of direct action organizing because they put real stakes and material wealth at the crux of what is being discussed. Sometimes people think that all this conversation, symbolism and talk about labor inequalities and collective organizing don’t do anything, but in my mind as a communication person, you have to create that consciousness and idea in people’s heads before they can get to direct action and strikes.

As we watch media related to this issue, how has American media historically influenced or interacted with strikes and movements?

We live in a divergent media environment where there are so many media echo chambers. That pertains to this current strike because, really, what’s going on is a strike against the global media conglomerates like Disney, Discovery, Netflix, etc. If those conglomerates are the only ones producing news about the strikes, there’s a chance that some of the news media, such as CBS, ABC, FOX, CNN or even cable news, aren’t holistically reporting on everything that’s going on with the strikes. But that’s not different from the history of how you see corporate media report on strikes.

The good thing about today’s media environment is that you have media options where you can potentially learn more about what’s going on in those realms. You have union members or other content makers publishing media and stories about this stuff so you can learn more than what’s catching headlines in the Houston Chronicle or The New York Times. That’s completely different from when people only had access to corporate news outlets. In the major mainstream corporate media, we’re only seeing what comes to the top and not the broad spectrum of everything that’s going on.

What can we learn from this strike regarding the structure and makeup of the film and television industry?

I think a lot of people don’t understand that the industry of media — let’s say Hollywood, for example — is a working environment. Obviously, it's tied to celebrity and popular culture, but there’s a false consciousness that everybody in Hollywood is making the money that a Tom Cruise or Christopher Nolan, etc., is making. But that’s only 1%. The majority of writers get paid less than actors and directors. We’re seeing all of those people on TV and in the news, but we never really understand that the people who are really getting paid big money are the corporate owners, like Bob Iger who, I think, takes home $200 million over five years. That’s way more money than anybody will get.

In order to get health benefits through the actor’s union, an actor has to make at least $26,000 per year. Seventy percent of actors don’t make that much. A lot of writers, actors and content creators have part-time jobs outside of their entertainment industry pursuits. When you see somebody become a celebrity, that’s a fraction of the 70,000 people in the union. Everybody else is a working-class person.

Content creators don’t get any residual pay from the money being made in the streaming environment. The current strike is a way for us to learn about our current corporate capitalistic structure of not just the media and content industries, but also how to align these labor realities to the history of the autoworkers, educators and hotel and restaurant worker movements in this country.

What are the challenges for workers when negotiating with large corporations?

Corporations are very powerful. One aspect of their power has been their ability to create political lobbies in D.C. and advocate for corporations to be considered citizens themselves. I think that’s one thing the American public needs to understand — corporations have a lot of protection and have been able to pay political lobbyists to go to D.C. and advocate for their interests and therefore create laws that protect their corporations.

That’s completely opposite from an ideal democratic society. We may believe in the myth that everyday citizens participate in government, but everyday people work and don’t have the money or time to go to D.C. to create lobbies. That only really happens when we see big protests happening in front of the Capitol, such as the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in the ’60s. Or when workers unionize and pool resources to advocate in local, state and federal levels. One thing to understand is that these media corporations are advocating for their interests on an everyday basis. The reason why the entertainment dual strike is important is because it gets the public’s eye on the need to make this a labor issue as well.

As an educator who’s in classrooms and writes about this stuff, I often run into students, faculty and staff who feel that being politically active isn’t something that is worthwhile. I think students in particular need to understand that being political is normal and that banding together to create collective politics is important. Collective politics and union strikes are important because they hold those in power accountable at the end of the day.