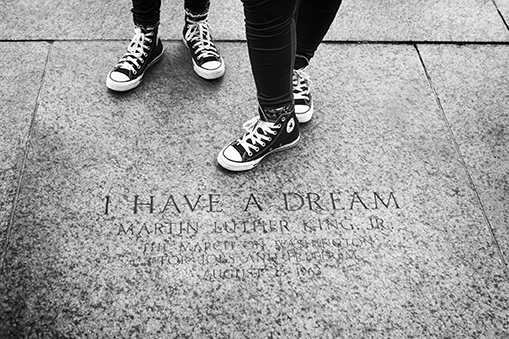

The third Monday of every January is Martin Luther King Jr. Day, and this year marks the 30th anniversary of the federal holiday honoring the activist’s lifelong contributions to civil rights and social justice. King promoted nonviolent tactics, such as the March on Washington in 1963, and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964.

What is often overlooked, however, is that King was also an intelligent writer. Though he wrote his own sermons and speeches, history tends to focus on his oratory skills. However, according to Dr. Ira Dworkin from the Department of English, his use of the written word was fundamental in driving the movement forward.

“Activists such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X were both extremely accomplished writers,” said Dworkin, an associate professor specializing in African American and African diaspora literature. “Many figures of the era who are best known as creative writers were also activists.”

Literature played a significant role in documenting the marginalization of Black Americans and spreading awareness of the reality of racism and racial injustice.

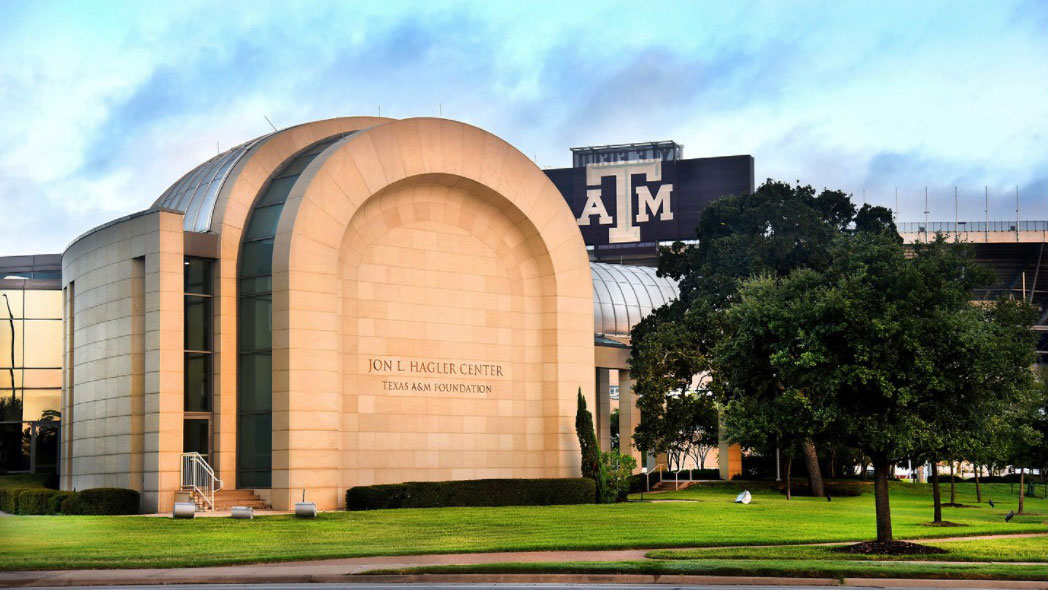

“There are countless Black authors who were instrumental in the Civil Rights Movement,” Dworkin said. “Their words feature prominently in literature classes at Texas A&M University and beyond. Most significantly, the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s was a critical formation of poets, playwrights, artists and activists. These writers developed a creative sensibility and practice that was embedded within collaborative social movements.”

This intersection of art and activism is evident in the era’s most influential publications, he said.

“For example, many of the era’s newspapers and magazines like Freedomways, Umbra, The Liberator, Black Dialogue, Soulbook and Negro Digest [later called Black World] featured literary genres alongside various forms of political rhetoric and commentary,” he said.

There are countless Black authors who were instrumental in the Civil Rights Movement...These writers developed a creative sensibility and practice that was embedded within collaborative social movements.

However, despite these platforms, many writers faced challenges in getting published, as mainstream publishers often ignored or outright rejected work deemed too political or radical.

“Throughout the history of the United States, Black writers have faced extreme challenges getting their work published by mainstream white publishers,” Dworkin said. “One of the most interesting and important exceptions within the world of white publishing is the case of Nobel laureate Toni Morrison who worked from 1967 to 1983 as an editor at Random House.”

Dworkin considers it both ironic and troubling that today, Morrison is perhaps one of the most decorated U.S. writers of the past century but also one of the most censored. Despite this, he believes Morrison's work remains deeply relevant, continuing to engage readers in crucial conversations about race, justice and equality.

Dworkin notes that these challenges are also evident in the work of the late Henry Dumas, whose life was tragically ended when he was killed by a New York transit officer in May 1968, only two months after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. Dumas was featured in Black Fire, which included his poem “mosaic harlem” and references to Martin Luther King Jr. as part of a broader multifaith Black tradition.

“The example of Dumas reminds us that writers are members of the Black community and are impacted by state violence whether they are writers or not,” Dworkin said.