In an era of instant updates and immediate access to information, it's easy to overlook the long history of efforts to make knowledge available to everyone. While the internet, social media and digital publishing may feel like modern inventions, they echo earlier literary movements, particularly those from the 17th and 18th century.

Dr. Margaret Ezell, a distinguished professor in the Department of English, has spent much of her career researching early modern print and manuscript culture as well as the evolution of authorship.

“My focus is primarily on the late 17th and early 18th centuries,” Ezell said. “I am not a scholar of contemporary digital culture, but I just happened to notice these things because it's everywhere around me.”

In her latest open-access work, Early English Periodicals and Early Modern Social Media, Ezell parallels the literary culture of English periodicals in the late 17th and early 18th century with a similar circulation of knowledge that is seen today with emerging social media platforms.

In the wake of the printing press, English periodicals developed as a distinct literary genre that had a relationship with its readers, setting it apart from the newspapers of the time.

“The first English newspaper, the London Gazette, was published by the British government in 1665,” Ezell said. “It included only official news, such as reports from shipping companies or foreign countries.”

In contrast, bookseller John Dunton took a different approach in 1690 by creating a “question-answer” periodical, The Athenian Mercury. Unlike the Gazette, which was influenced by government authority, The Athenian engaged its readers directly, answering their submitted questions that ranged from “What language did Adam and Eve speak?” to “Is the sun a mass made of liquid gold?”

“This is a genre whose content is created and shared by the readers,” Ezell said. “This would be the equivalent platform of early Facebook or Myspace.”

It is literary culture in which the readers actively participate in the creation and dissemination of knowledge—an essential aspect of what Ezell calls “social authorship.” In her latest work, Ezell revisits her 1999 study, where she first coined the term "social authorship" to describe an interactive literary exchange that was not motivated by profit.

“Readers were also writers, editors and curators, not merely passive, paying consumers,” she said. “It was a form of authorship later often overlooked, the way people continued to circulate works in handwritten manuscript form.”

Despite a burgeoning print market, circulating work in the late 17th century remained popular.

“It was a better technology to do it in handwritten copies because the number of presses in England in the 17th and 18th century was restricted," Ezell said, “and if you lived outside of London or a University city, well, good luck to you.”

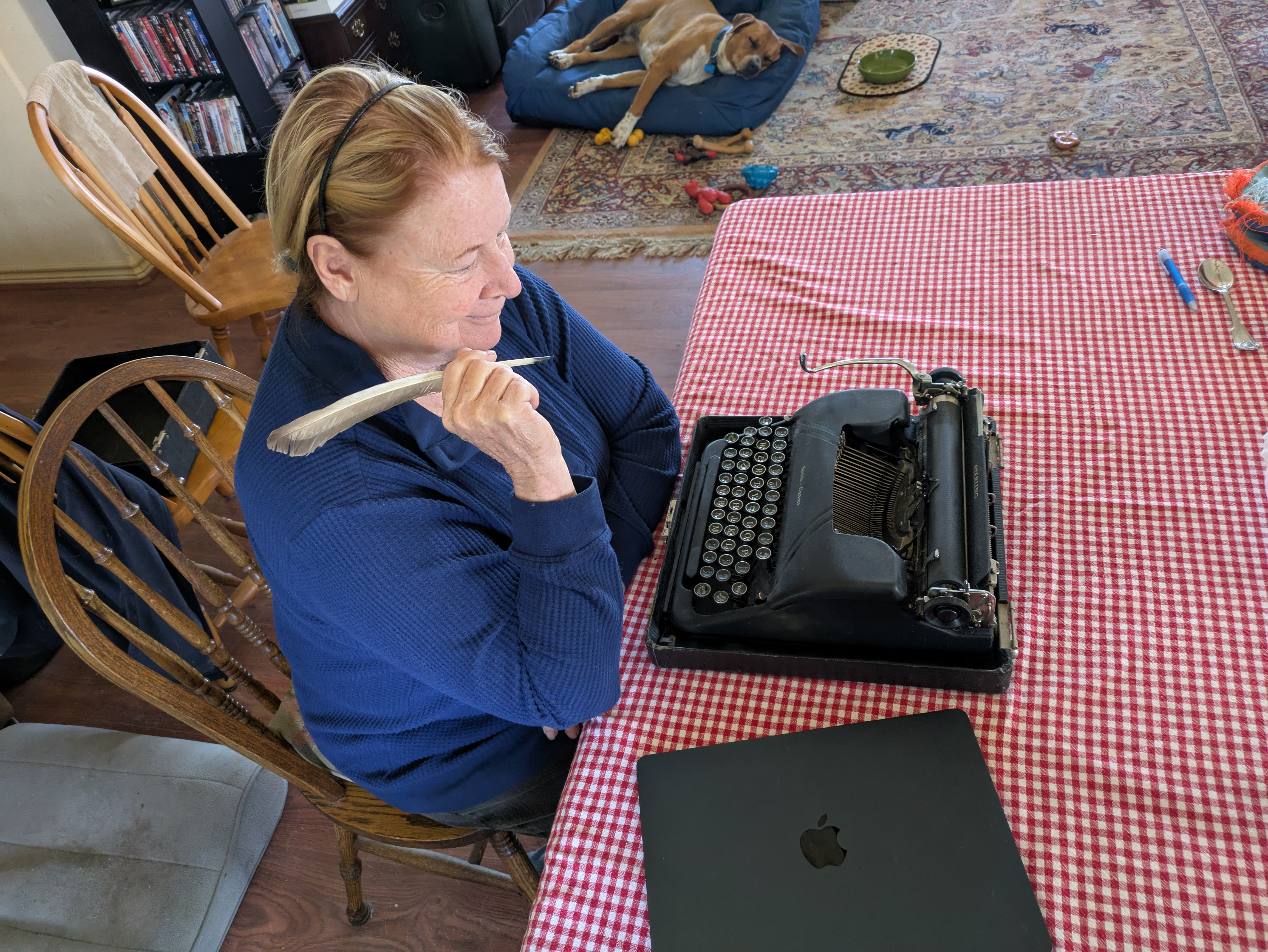

Ezell sees parallels in her own professional history.

“When I started working at Texas A&M in 1982, we all had typewriters,” she said. “Despite receiving computers, I kept a typewriter in my office for 10 years because there was no easy mechanism at the time for printing envelopes. It’s the same thing that you see in the 17th and early 18th century. If you wanted people to read your poetry, you were better off making several copies and sending them to your friends. And it's social. It's not to make money.”

In her 1999 study, Ezell compared social authorship to emerging digital media. Now, two decades later, she extends that comparison to the commercialized nature of the periodical.

“What you start seeing happening with the Athenian Mercury is a bookseller would provide a platform so he can make money off of your content,” Ezell said. “There had to be an audience that was interested in it, and he then had to persuade them they wanted to continue buying it.”

In her study, Ezell argues that social media, much like early manuscript culture, began as a platform for sharing, but eventually evolved into a business practice, much like the periodicals.

“It would sort of be a little bit, again, like the beginning of Facebook where you had friends and supposedly only your friends saw what you wrote,” Ezell said. “But now of course, people have 80,000 friends and they make money off their friends.”

However, by acknowledging the continuing prevalence of manuscript culture, Ezell challenges the notion of an abrupt, “light switch” theory of change. Ezell’s work shows that while technology evolves, it doesn’t immediately drastically change the core of how and why humans create and share their ideas.

“It was then never just either print or handwriting and it’s now never only electronic or print,” Ezell said, “Cultures don’t change like that. What works will survive and what doesn't work will slowly be replaced. I no longer address envelopes on a manual typewriter in my office because email is now the better technology for sending correspondence; maybe my computer and printer can do it now, but I don’t know how, so if I address an envelope, I do it in handwriting!”