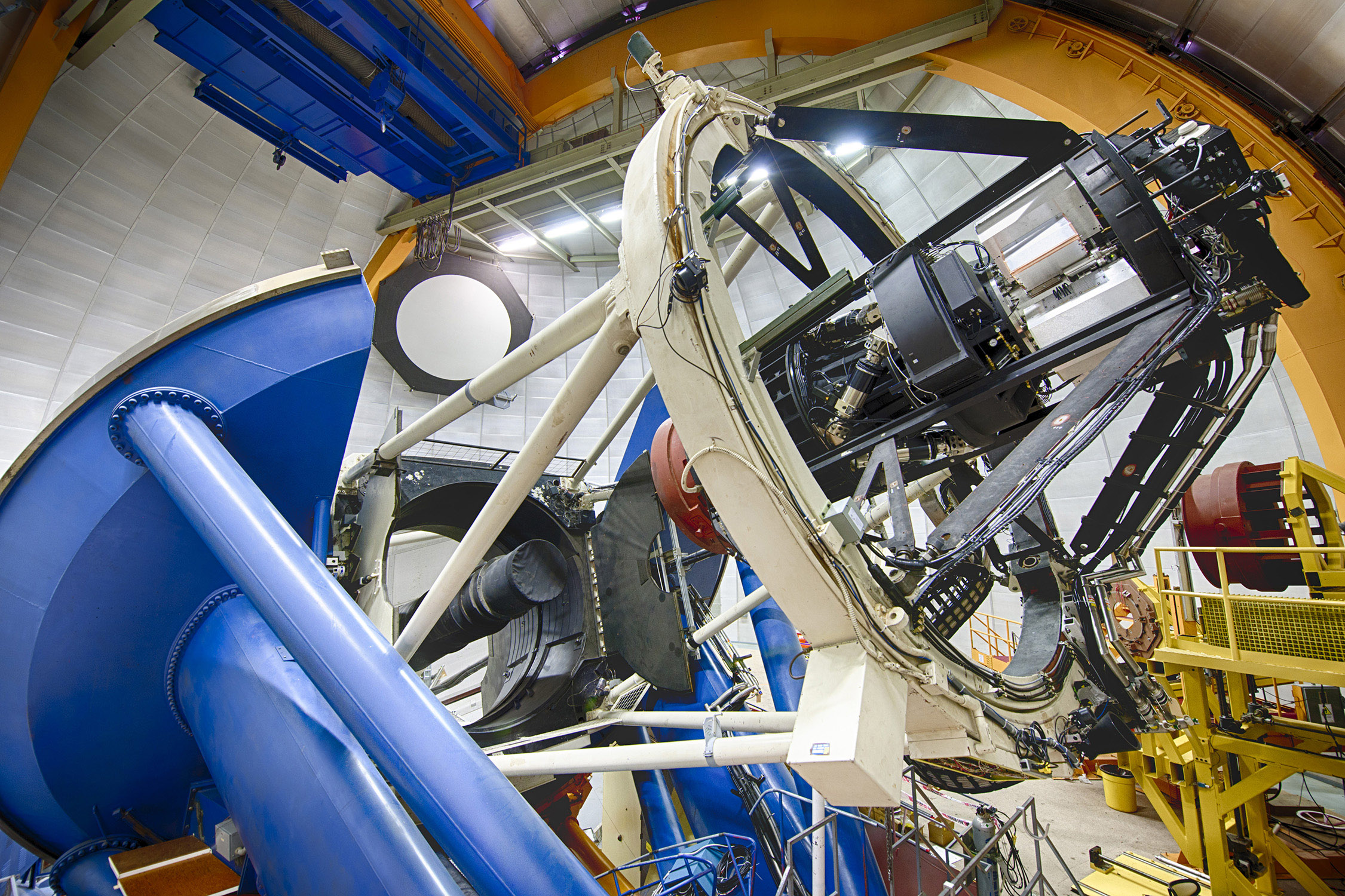

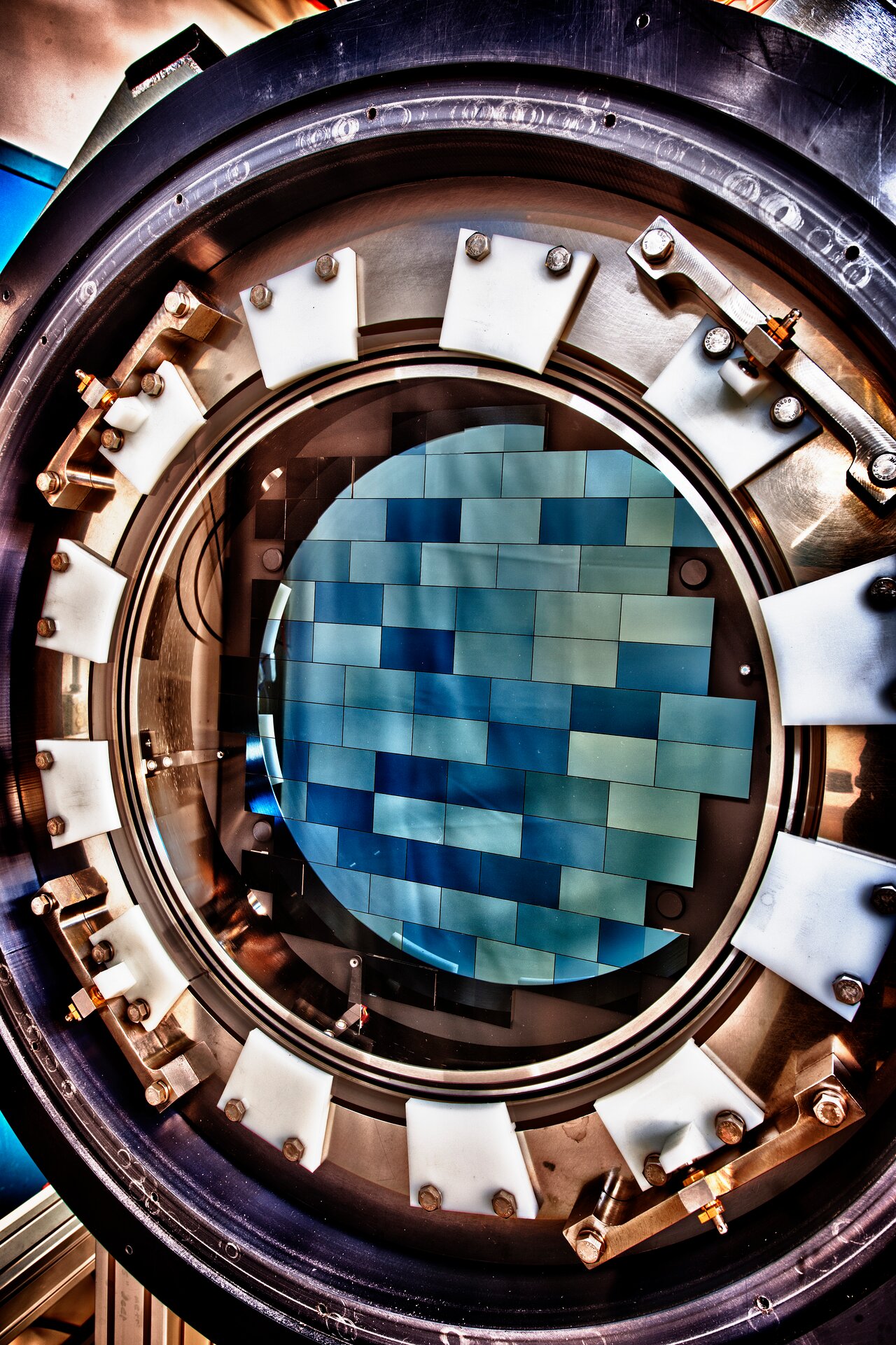

As an undergraduate civil-engineering-turned-physics major at MIT, Texas A&M University astronomer Dr. Darren DePoy worked on one of the first digital cameras ever used in astronomy, long before the advent of the term “digital camera” or becoming project scientist for the one formerly recognized as the world’s largest that powered the Dark Energy Survey (DES) from 2013 to 2019.

For almost as long as DePoy and fellow Texas A&M astronomer Dr. Jennifer Marshall have been at Texas A&M as members of the Department of Physics and Astronomy and George P. and Cynthia Woods Mitchell Institute for Fundamental Physics and Astronomy, they have been involved with the DES along with some of the world’s biggest projects in their quest to position Texas A&M as a global leader in astronomical instrumentation. In the process, they have helped educate untold numbers of Texas A&M students across disciplines while introducing them to unprecedented hands-on opportunities spanning teaching, research and service.

Marshall got her own opportunity to witness cosmic history in August 2017, courtesy of DES and that digital camera, known as DECam. She used the 570-megapixel marvel mounted atop the 4-meter Victor M. Blanco Telescope at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory to capture some of the initial images of the first confirmed explosion from two colliding neutron stars ever seen by astronomers. Whether fate or poetic justice, it made perfect sense, considering that one of DECam’s key sub-components — a spectrophotometric calibration system known as DECal that enabled the camera to obtain very high precision brightness measurements of the objects it saw as it surveyed a 5,000-square degree area of the southern sky — was built within the Charles R. ’62 and Judith G. Munnerlyn Astronomical Laboratory, which she and DePoy manage.

Another Decade, Another DES Development

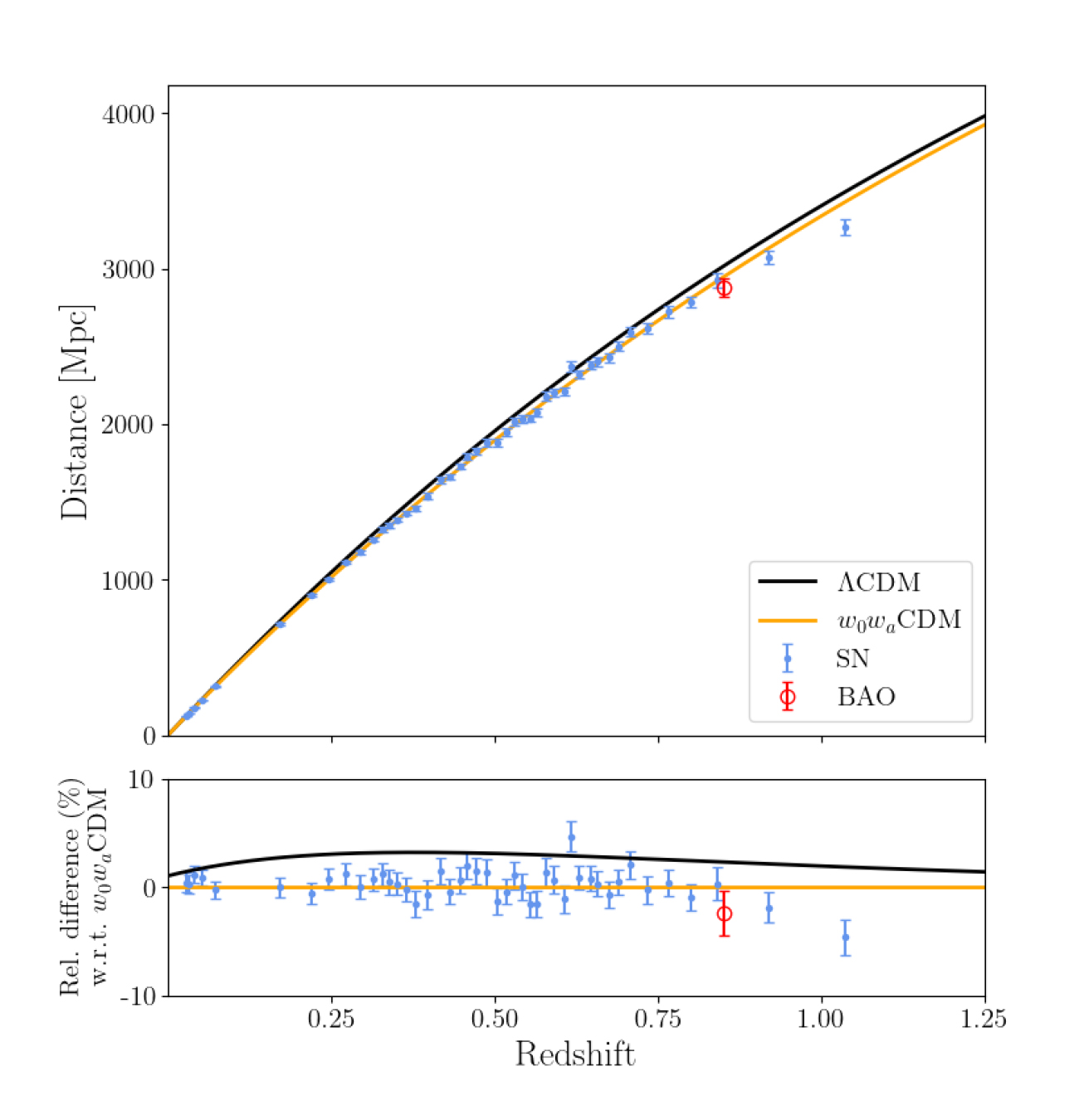

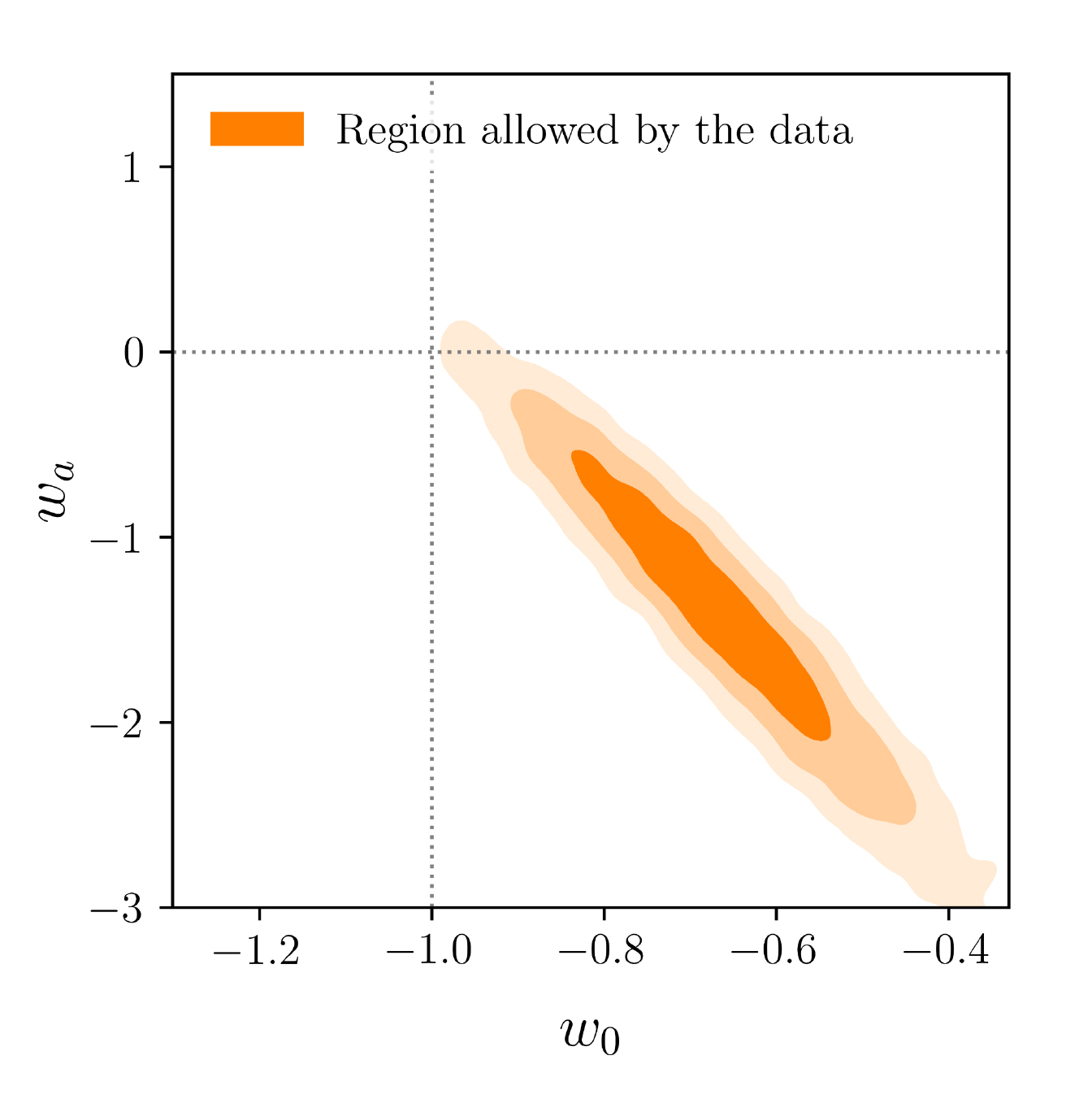

A decade after releasing the first in its series of dark matter maps of the cosmos at the American Physical Society April 2015 Meeting, DES scientists once again have made headlines during this week's Global Physics Summit 2025 in Anaheim, sharing their findings there in multiple March 19 presentations and in a paper appearing on the online repository arXiv indicating potential inconsistencies in the standard model of cosmology. Their research combines the constraints from two of the DES’s four primary methods of studying dark energy — distance measurements made using Type Ia supernovae and a feature in the statistical distribution of galaxies called the baryon acoustic oscillation (BAO) scale that measures the expansion history of the universe using sound waves — to produce what Marshall describes as “a potentially very impactful result” pointing to evolving dark energy as a determining factor.

“Astronomers at Texas A&M have been working on the DES project from the beginning, first in the Munnerlyn Lab where we built the hardware that enabled the most precise measurements ever made of the universe, and now participating in producing these exciting cosmological results that could lead to a new physics describing the structure of the universe,” said Marshall, an associate professor and holder of the Arseven-Mitchell Chair in Astronomical Statistics.

To date, only 5% of the universe’s content has been defined, known as ordinary matter that forms us and our surroundings. The remaining 95% is made up of two exotic entities that have never been produced in the laboratory and whose physical nature is still unknown — dark matter, which accounts for 25% of the content of the cosmos, and dark energy, which contributes 70%. In the standard model of cosmology, dark energy is the cosmological constant, or energy of empty space, and its density remains constant throughout the evolution of the universe. However, a new result such as the one unveiled this week by DES scientists could indicate a time-changing dark energy capable of evolving in tandem with the universe along with the forces and properties that define it.

“The possibility that key cosmological parameters have changed over time suggests that new physics shapes the structure and evolution of the universe,” said DePoy, deputy director of the Mitchell Institute and inaugural holder of the Rachal-Mitchell-Heep Endowed Professorship in Physics who also serves as associate dean for infrastructure in the College of Arts and Sciences. “The ultimate outcome of these results, if confirmed, could be a new understanding of how the universe began and became what we see today. Subsequent developments could lead to products and capabilities we can only guess at today, much like early investigations of the cosmic microwave background eventually helped in the development of cell phone technology.”

Eyes On The Skies And Ultimate Prize

While the results are a culmination of years of collaborative work and analysis by experts across the globe, Marshall cautions they are preliminary and not yet significant enough to rise to the claim of a discovery. Still, she admits the tantalizing prospect of a time-evolving dark energy is intriguing and a good reminder of the scientific inspiration she found as an undergraduate involved in both geology and astronomy research at Northwestern University.

“I built an instrument that I used to calibrate a submillimeter polarimeter at the South Pole,” Marshall recalled. “I had built things out of wood many times with my father growing up but combining that with scientific study was not something I had ever considered. And yet, as an undergraduate, I got to build something, go to the South Pole and get paid to do science. I was hooked.”

As the treasure trove of DES-related results winds down, Marshall says it’s likely there will be one more significant push along with a related announcement in roughly a year that will be based on all six years of DES data. But for her, the results far closer to home already speak for themselves.

“Our involvement in DES has led to five astronomy Ph.D.s and research experiences for many dozens of undergraduate student researchers at Texas A&M,” Marshall said. “One of our first graduate students, Dr. Ting Li, worked to develop the calibration techniques for the project, launching her outstanding academic career. She is now a professor at the University of Toronto, where she leads a very successful DES follow-up project, the Southern Stellar Stream Spectroscopic Survey, or S5.”

Cosmological Constraints And Career Trajectories

For a career astrophysicist who credits the late astronomer and instrumentation pioneer Dr. Vera C. Rubin as one of his initial inspirations dating back to the inaugural trip she took him on as an undergraduate to an astronomical observatory — in Chile, no less — DePoy finds it particularly gratifying that the Rubin/Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST) is one of the many projects now on Texas A&M’s near horizon, thanks in no small part to a road not traveled — a 1982 job offer from Schlumberger that he decided to turn down in favor of studying astrophysics at the University of Hawaii. Five years later, he earned his doctorate in astronomy and never looked back, spending 18 years building an astronomy program at The Ohio State University — where Marshall earned her Ph.D. in astronomy — before making the leap to help do the same at Texas A&M.

DES was the first big project I joined after moving to Texas A&M in 2008. The initial investment in laboratory infrastructure in College Station has led to significant scientific results in a very prominent cosmology project.

In another timely tie-in earlier this month, the Rubin Observatory team on Cerro Pachón in Chile lifted the car-sized LSST Camera that succeeded DePoy’s DECam as the world’s largest digital camera into position on the Simonyi Survey Telescope — a significant step in the LSST’s ambitious universal mission to capture more data than any previous survey in astronomical history.

“DES was the first big project I joined after moving to Texas A&M in 2008,” DePoy said. “The initial investment in laboratory infrastructure in College Station has led to significant scientific results in a very prominent cosmology project. Continuing to run the lab and participate in these kinds of major astronomical surveys, such as the Giant Magellan Telescope, the Hobby-Eberly Telescope Dark Energy Experiment, the Multi-Object Optical and Near-IR Spectrograph and the Maunakea Spectroscopic Explorer in addition to the DES and Rubin/LSST, will continue to strengthen the astronomy program at Texas A&M along with our students and broader teaching, research and service mission. All of us are excited to be part of such groundbreaking projects with such broad potential to help shape the future of astronomy.”